Invertebrate Integument

Invertebrate Integument

Many protozoa have only the delicate cell or plasma membranes for external coverings; others, such as Paramecium, have developed a protective pellicle. Most multicellular invertebrates, however, have more complex tissue coverings. The principal covering is a single-layered epidermis. Some invertebrates have added a secreted noncellular cuticle over the epidermis for additional protection.

The molluscan epidermis is delicate and soft and contains mucousglands, some of which secrete the calcium carbonate of the shell. Cephalopod molluscs (squids and octopuses) have developed a more complex integument, consisting of cuticle, simple epidermis, layer of connective tissue, layer of reflecting cells (iridocytes), and thicker layer of connective tissue.

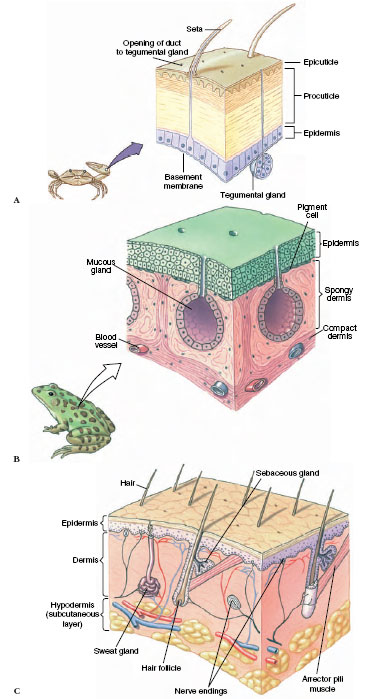

Arthropods have the most complex of invertebrate integuments, providing not only protection but also skeletal support. Development of a firm exoskeleton and jointed appendages suitable for attachment of muscles has been a key feature in the extraordinary diversity of this phylum, the largest of animal groups. Arthropod integument consists of a single-layered epidermis (also called more precisely hypodermis), which secretes a complex cuticle of two zones (Figure 31-1A). The thicker inner zone, the procuticle, is composed of protein and chitin (a polysaccharide) laid down in layers (lamellae) much like veneers of plywood. The outer zone of cuticle, lying on the external surface above the procuticle, is the thin epicuticle. The epicuticle is a nonchitinous complex of proteins and lipids that provides a protective moisture-proofing barrier to the integument.

Arthropod cuticle may remain as a tough but soft and flexible layer, as it is in many microcrustaceans and insect larvae. However, it may be hardened by either of two ways. In the decapod crustaceans, for example, crabs and lobsters, the cuticle is stiffened by calcification, the deposition of calcium carbonate in the outer layers of the procuticle. In insects hardening occurs when protein molecules bond together with stabilizing cross-linkages within and between adjacent lamellae of the procuticle. The result of this process, called sclerotization, is formation of a highly resistant and insoluble protein, sclerotin. Arthropod cuticle is one of the toughest materials synthesized by animals; it is strongly resistant to pressure and tearing and can withstand boiling in concentrated alkali, yet it is light, having a specific mass of only 1.3 (1.3 times the weight of water)

When arthropods molt, the epidermal cells first divide by mitosis. Enzymes secreted by the epidermis digest most of the procuticle. The digested materials are then absorbed and consequently are not lost to the body. Then in the space beneath the old cuticle a new epicuticle and procuticle are formed. After the old cuticle is shed, the new cuticle is thickened and calcified or sclerotized.

|

| Figure 31-1 Integumentary systems of animals, showing the major layers. A, Structure of arthropod (crustacean) body wall showing cuticle and epidermis. B, Structure of amphibian (frog) Epicuticle integument. C, Structure of human integument. |

Many protozoa have only the delicate cell or plasma membranes for external coverings; others, such as Paramecium, have developed a protective pellicle. Most multicellular invertebrates, however, have more complex tissue coverings. The principal covering is a single-layered epidermis. Some invertebrates have added a secreted noncellular cuticle over the epidermis for additional protection.

The molluscan epidermis is delicate and soft and contains mucousglands, some of which secrete the calcium carbonate of the shell. Cephalopod molluscs (squids and octopuses) have developed a more complex integument, consisting of cuticle, simple epidermis, layer of connective tissue, layer of reflecting cells (iridocytes), and thicker layer of connective tissue.

Arthropods have the most complex of invertebrate integuments, providing not only protection but also skeletal support. Development of a firm exoskeleton and jointed appendages suitable for attachment of muscles has been a key feature in the extraordinary diversity of this phylum, the largest of animal groups. Arthropod integument consists of a single-layered epidermis (also called more precisely hypodermis), which secretes a complex cuticle of two zones (Figure 31-1A). The thicker inner zone, the procuticle, is composed of protein and chitin (a polysaccharide) laid down in layers (lamellae) much like veneers of plywood. The outer zone of cuticle, lying on the external surface above the procuticle, is the thin epicuticle. The epicuticle is a nonchitinous complex of proteins and lipids that provides a protective moisture-proofing barrier to the integument.

Arthropod cuticle may remain as a tough but soft and flexible layer, as it is in many microcrustaceans and insect larvae. However, it may be hardened by either of two ways. In the decapod crustaceans, for example, crabs and lobsters, the cuticle is stiffened by calcification, the deposition of calcium carbonate in the outer layers of the procuticle. In insects hardening occurs when protein molecules bond together with stabilizing cross-linkages within and between adjacent lamellae of the procuticle. The result of this process, called sclerotization, is formation of a highly resistant and insoluble protein, sclerotin. Arthropod cuticle is one of the toughest materials synthesized by animals; it is strongly resistant to pressure and tearing and can withstand boiling in concentrated alkali, yet it is light, having a specific mass of only 1.3 (1.3 times the weight of water)

When arthropods molt, the epidermal cells first divide by mitosis. Enzymes secreted by the epidermis digest most of the procuticle. The digested materials are then absorbed and consequently are not lost to the body. Then in the space beneath the old cuticle a new epicuticle and procuticle are formed. After the old cuticle is shed, the new cuticle is thickened and calcified or sclerotized.