Sex Determination

Sex Determination

Before the importance of chromosomes

in heredity was realized in the early

1900s, how gender was determined was

totally unknown. The first really scientific

clue to the determination of sex

came in 1902 when C. McClung

observed that bugs (Hemiptera) produced

two kinds of sperm in approximately

equal numbers. One kind contained

among its regular set of

chromosomes a so-called accessory

chromosome that was lacking in the

other kind of sperm. Since all the eggs

of these species had the same number

of haploid chromosomes, half the

sperm would have the same number of

chromosomes as the eggs, and half of

them would have one chromosome

less. When an egg was fertilized by a

spermatozoon carrying the accessory

(sex) chromosome, the resulting offspring

was a female; when fertilized by

the spermatozoon without an accessory

chromosome, the offspring was a male.

Therefore a distinction was made

between sex chromosomes, which

determine sex (and sex-linked traits);

and autosomes, the remaining chromosomes,

which do not influence sex.

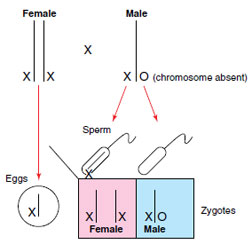

The particular type of sex determination

just described is often called the XX-XO

type, which indicates that the females

have two X chromosomes and the

males only one X chromosome (the O

indicates absence of the chromosome).

The XX-XO method of sex determination

is depicted in Figure 5-3.

Speculation on how sex was determined in animals produced several incredible theories, for example,that the two testicles of the male contained different types of semen,one begetting males, the other females. It is not difficult to imagine the abuse and mutilation of domestic animals that occurred when attempts were made to alter the sex ratios of herds. Another conjecture asserted that sex of the offspring was determined by the more heavily sexed parent. An especially masculine father should produce sons, an effeminate father only daughters.Such mistaken ideas have lingered until recently.

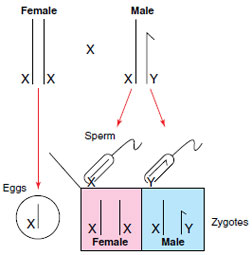

Later, other types of sex determination

were discovered. In humans and

many other animals each sex contains

the same number of chromosomes;

however, the sex chromosomes (XX)

are alike in the female but unlike (XY)

in the male. Hence the human egg contains

22 autosomes + 1 X chromosome.

The sperm are of two kinds; half carry

22 autosomes + 1 X and half bear 22

autosomes + 1 Y. The Y chromosome

is much smaller than the X and carries

very little genetic information. At fertilization,

when the 2 X chromosomes

come together, the offspring are female;

when X and Y come together, the offspring

are male. The XX-XY kind of

determination is shown in Figure 5-4.

A third type of sex determination is found in birds, moths, butterflies, and some fish in which the male has 2 X (or sometimes called ZZ) chromosomes and the female an X and Y (or ZW). Finally, there are both invertebrates and vertebrates in which sex is determined by environmental or behavioral conditions rather than by sex chromosomes, or by genetic loci whose variation is not associated with visible difference in chromosomal structure.

In the case of X and Y chromosomes, the homologous chromosomes are unlike in size and shape. Therefore, they do not both carry the same genes. The genes of the X chromosome often do not have allelic counterparts on the diminutive Y chromosome. This fact is very important in sex-linked inheritance, which we shall discuss later.

We now know that not all animals with dioecious reproduction have their genders determined chromosomally. Several invertebrate examples are known. Many fishes and reptiles lack sex chromosomes altogether; in these organisms, gender is determined by nongenetic factors such as temperature or behavior. In crocodilians, many turtles, and some lizards the incubation temperature of the nest determines the sex ratio by some as yet unknown sex-determining mechanism. Alligator eggs, for example, incubated at low temperature become all females; those incubated at higher temperature become all males. Sex determination of many fishes depends on behavior. Most of these species are hermaphroditic, possessing both male and female gonads. Sensory stimuli from the animal’s social environment determine whether it will be male or female.

|

| Figure 5-3 XX-XO sex determination. |

Speculation on how sex was determined in animals produced several incredible theories, for example,that the two testicles of the male contained different types of semen,one begetting males, the other females. It is not difficult to imagine the abuse and mutilation of domestic animals that occurred when attempts were made to alter the sex ratios of herds. Another conjecture asserted that sex of the offspring was determined by the more heavily sexed parent. An especially masculine father should produce sons, an effeminate father only daughters.Such mistaken ideas have lingered until recently.

|

| Figure 5-4 XX-XY sex determination. |

A third type of sex determination is found in birds, moths, butterflies, and some fish in which the male has 2 X (or sometimes called ZZ) chromosomes and the female an X and Y (or ZW). Finally, there are both invertebrates and vertebrates in which sex is determined by environmental or behavioral conditions rather than by sex chromosomes, or by genetic loci whose variation is not associated with visible difference in chromosomal structure.

In the case of X and Y chromosomes, the homologous chromosomes are unlike in size and shape. Therefore, they do not both carry the same genes. The genes of the X chromosome often do not have allelic counterparts on the diminutive Y chromosome. This fact is very important in sex-linked inheritance, which we shall discuss later.

We now know that not all animals with dioecious reproduction have their genders determined chromosomally. Several invertebrate examples are known. Many fishes and reptiles lack sex chromosomes altogether; in these organisms, gender is determined by nongenetic factors such as temperature or behavior. In crocodilians, many turtles, and some lizards the incubation temperature of the nest determines the sex ratio by some as yet unknown sex-determining mechanism. Alligator eggs, for example, incubated at low temperature become all females; those incubated at higher temperature become all males. Sex determination of many fishes depends on behavior. Most of these species are hermaphroditic, possessing both male and female gonads. Sensory stimuli from the animal’s social environment determine whether it will be male or female.