Bacterial diarrhoeal disease

Infectious diarrhoea is common and a very important cause of morbidity and mortality in children under 5 years worldwide. The gut is protected by gastric acid, bile salts, the mucosal immune system and inhibitory substances that are produced by the normal flora.Epidemiology

Organisms are transmitted by hands and fomites (faecal-oral route), by food or water. The infective dose can be as few as 10 organisms (Shigella). Some foods (e.g. milk) or drugs (e.g. H2 antagonists and proton pump inhibitors) may reduce the protective effects of gastric acid.

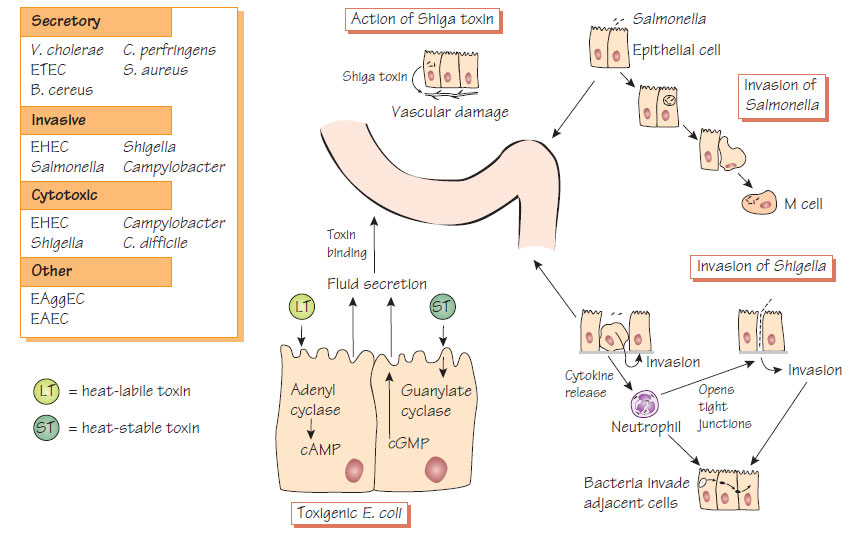

- Toxin-mediated dysregulation of intestinal cells causing fluid secretion.

- Invasion of the intestinal wall occurs with destruction of the cells (see Figure).

- Secretory diarrhoea produces infrequent large-volume stools as the absorptive capacity of the colon is overwhelmed.

- In dysenteric illness (e.g. Shigella), colonic inflammation causes a loss in bowel capacity and frequent, often blood-stained stools.

- Enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) produce Shiga toxin (Stx), which causes bloody diarrhoea and the haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), which is commonest with serotype O157:H7.

- There may be many small stools (typical of large-bowel infection) or infrequent large stools (small-intestinal infection). Stools may be blood stained when there is destruction of the intestinal mucosa, or have a fatty consistency and offensive smell if malabsorption is present.

- Dehydration and electrolyte imbalance may develop rapidly with potentially fatal results, especially in cholera. Crampy abdominal pain may accompany diarrhoea (e.g. Campylobacter and Shigella infections); this may mimic acute abdominal conditions, such as appendicitis.

- Fever is not always present.

- Septicaemia can occur in salmonellosis, but is rare in other diarrhoeal diseases.

- Secondary lactose intolerance, which is caused by loss of intestinal lactase, may persist for a few weeks.

- Patients with IgA deficiency may have difficulty eradicating Giardia; those with T-cell deficiency are prone to Salmonella and Cryptosporidium (see Infections in immunocompromised patients).

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis is by culture using a range of media specific to different groups of pathogens.

- Multiplex nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are being introduced into routine practice.

- Organisms should be typed using molecular methods for epidemiological purposes (see Structure and classification of bacteria).

- Toxin may be detected in stool samples (e.g. Clostridium difficile toxin).

The management of diarrhoeal disease is based on adequate fluid replacement and correction of electrolyte imbalances. Despite the high outflow found in secretory diarrhoea, fluid absorption still occurs. Oral rehydration solutions that consist of 150-155 mmol/L sodium and 200-220 mmol/L glucose can be life-saving. Intravenous fluid replacement is rarely necessary. Antimotility drugs are of no benefit and may be dangerous, especially in small children. Oral antibiotics, such as tetracycline or ciprofloxacin, which shorten the duration of symptoms, may be of benefit in cholera and other cases of severe fluid diarrhoea. Patients with severe dysentery and salmonellosis should be treated with ciprofloxacin or co-trimoxazole. Renal failure due to HUS following E. coli O157 requires specialist management.

- Good sanitation is essential in preventing diarrhoeal disease.

- Animal husbandry and slaughter methods should be designed to prevent the introduction of animal intestinal pathogens into the human food chain.

- Food must be cooked to a sufficiently high temperature to kill pathogens and, if not eaten immediately, refrigerated at a low enough temperature to prevent any bacteria multiplying.

- Cooked food should be physically separated from uncooked food to prevent cross-contamination. This is especially true in institutional cooking (e.g. hospitals and restaurants), where many individuals might become infected following a single failure of hygiene.

- Travellers' diarrhoea can be reduced by careful choice of food while travelling.

- Oral, heat-killed and live attenuated cholera vaccines are licensed for use but the protection they provide is short-lived.

- Whole-cell vaccines, purified Vi polysaccharide vaccine and oral Ty21a vaccine are available against typhoid. New Vi conjugate vaccines are being developed.