Endocarditis, myocarditis and pericarditis

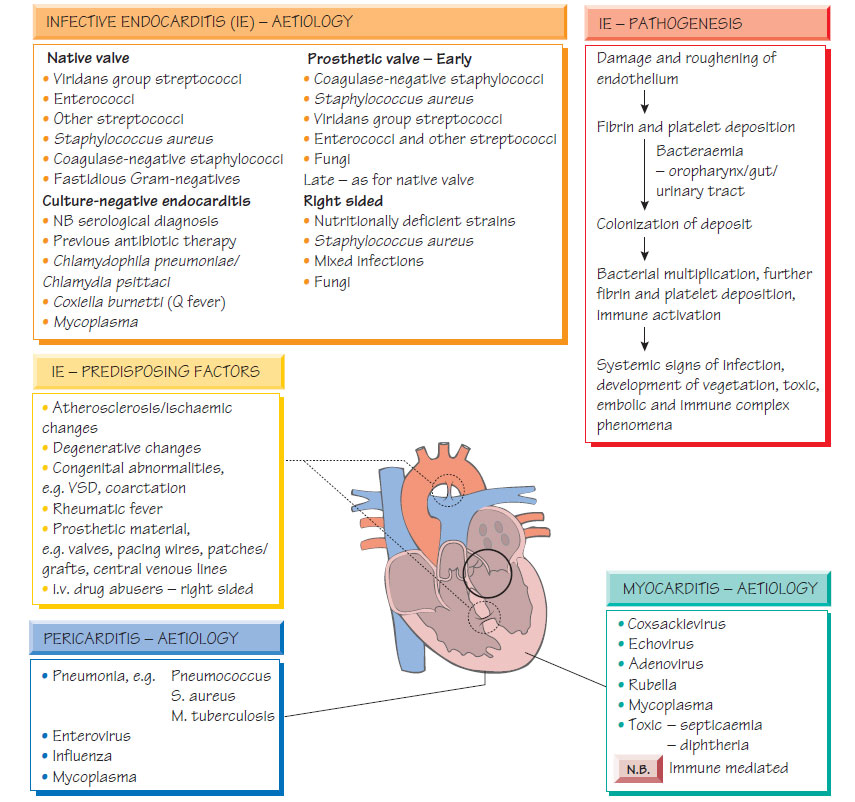

EndocarditisHeart valves may become infected during transient bacteraemia. Congenitally abnormal or damaged valves are at greatest risk. Bacteria may originate from the mouth, urinary tract, intravenous drug misuse or colonized intravascular lines.

Clinical features

- Malaise, fever and variable heart murmurs.

- Arthralgia.

- Classical stigmata (e.g. splinter haemorrhages, Osler's nodes, microhaematuria, retinal infarcts, finger clubbing, cafe-au-lait skin, and Janeway lesions) are only seen in long-standing infection.

- In the later stages, septic emboli may cause a stroke.

- With aggressive organisms (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus) disease progresses rapidly and valves may rupture.

A diagnosis is made if there are two major Duke criteria present or one major and three minor criteria. The major Duke criteria include: positive blood culture with characteristic organisms (e.g. viridans streptococci); persistently positive blood cultures with any organism; evidence of endocardial involvement demonstrated by echocardiogram; and new valvular regurgitation. Minor criteria include: predisposition; fever >38°C; immunological signs (e.g. septic pulmonary infarcts); and echocardiographic or microbiological evidence insufficient to be a major criterion.

- Local progression may lead to aortic root abscess.

- Valve destruction may lead to cardiac decompensation.

- Cerebral or limb infarction may follow septic embolus.

- Nephritis secondary to immune complex deposition can progress rapidly if sepsis is uncontrolled or if antibiotics with renal toxicity are given without care (e.g. aminoglycosides).

Investigation

Echocardiography, either transthoracic or transoesophageal (more sensitive), will demonstrate vegetations on the valves; a plain chest X-ray may show evidence of cardiac failure. At least three sets of blood cultures should be taken, an hour apart, while fever is present. Antibiotic therapy should await the results of blood culture if possible. Serum should be tested for antibodies to Coxiella, Bartonella and Chlamydia psittaci.

Ideally, antibiotics should not be commenced until the identity and sensitivities of the infecting organism are known; the prognosis of empirically treated, culture-negative endocarditis is poorer than that when the infecting organism is identified. Careful microbiological monitoring of the markers of inflammation (e.g. CRP) is associated with an improved outcome. Therapy is based on the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the antibiotics. If gentamicin is used concentrations must be monitored closely. Therapy is continued for 2-6 weeks depending on the organism and its susceptibility. Typical regimens include: benzylpenicillin and gentamicin for viridans streptococci; flucloxacillin and gentamicin for staphylococci; vancomycin and gentamicin for penicillin-allergic patients. National evidence-based guidelines for management should be followed. Surgical management may be required to deal with the haemodynamic consequences of endocarditis (e.g. valve rupture).

Antibiotic prophylaxis is given to patients with damaged valves when they undergo procedures that give rise to significant bacteraemia, such as dental work or urogenital surgery. For procedures that require an anaesthetic, prophylaxis is given at induction followed by subsequent oral doses. There are alternative regimens for penicillin allergy and prosthetic valves laid down by national guidelines.

Myocarditis

Most myocarditis is caused by viral infection, with enteroviruses being the commonest cause; however, it may complicate systemic viral infections, follow bacteraemia or form part of brucellosis, rickettsial or chronic Chagas infection.

- Presentation is with influenza-like symptoms associated with fatigue, exertional dyspnoea, palpitations and precordial pain.

- Tachycardia, dysrhythmia or cardiac failure may be present.

- The electrocardiogram (ECG) may show T-wave inversion, prolongation of the PR or QRS interval, extrasystoles or heart block.

- Other features include cardiomegaly on chest X-ray and elevated cardiac enzymes.

- The diagnosis is suggested by a temporal relationship between the viral symptoms and cardiological abnormalities.

- Viruses may be detected in faecal, nasopharyngeal and throat specimens (see DNA viruses: adenovirus, parvovirus and poxvirus) by nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs).

- Treatment is supportive.

Pericarditis is most often secondary to a non-infectious condition, such as myocardial infarction. It may complicate bacteraemia or follow spread of pus from an empyema (Streptococcus pneumoniae), or liver abscess (enterococci, Entamoeba histolytica). Tuberculosis can cause sub-acute pericarditis. Viral pericarditis is a self-limiting condition featuring fever, 'flu-like symptoms and sharp chest pain. Enteroviruses, especially coxsackie and influenza viruses, are most commonly implicated. The chest pain may vary with posture, swallowing or heartbeat. A pericardial rub may be heard. Cardiographic evidence of pericarditis may be demonstrated.

Patients with suppurative pericarditis present with fever, neutrophilia and signs of the underlying source of infection. Chest pain is severe and a fall in blood pressure may indicate developing tamponade. The ECG shows upward-curving elevated ST segments. Echocardiography will show pericardial thickening or effusion. Infection can be complicated by fibrosis and constrictive pericarditis, leading to congestive cardiac failure. Treatment is directed against the likely causative organism.