Pyrexia of unknown origin and septicaemia

Pyrexia of unknown originDefinition

An intermittent or persistent fever of >38.2°C lasting for more than 2 weeks and for which there is no obvious cause.

Aetiology

- Infection accounts for 45-55% (e.g. endocarditis, tuberculosis, hidden abscess).

- Malignancy accounts for 12-20% of cases (e.g. lymphomas or renal cell carcinoma).

- Connective tissue disorders account for 10-15% (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus or polyarteritis nodosum).

- Other causes to be considered include hypersensitivity to drugs, pulmonary emboli, granulomatous diseases (e.g. sarcoidosis), metabolic conditions (e.g. porphyria) and a factitious cause (i.e. fever induced deliberately by the patient).

- The longer the history of fever, the more likely it is that it arises from a non-infectious cause.

- A detailed history of the presenting complaint.

- Occupational and social history is important (e.g. vets and farmers are at risk of zoonotic infections, such as brucellosis).

- Travel may suggest exposure to unusual tropical infections.

- Sexual history may indicate possible HIV or related risks.

- Drug history must include those prescribed by a doctor or not, as some drugs and health products can cause fever.

- Patients may overlook vital information at the first interview; further opportunities for discussion are often necessary.

- The patient must be examined carefully for localized bone or joint pain, subtle rashes, lymphadenopathy, abdominal masses, cardiac murmurs and mild meningism.

- The physical examination should be repeated regularly to detect changes, such as development of a new cardiac murmur or enlargement of the liver that becomes palpable only at a later examination.

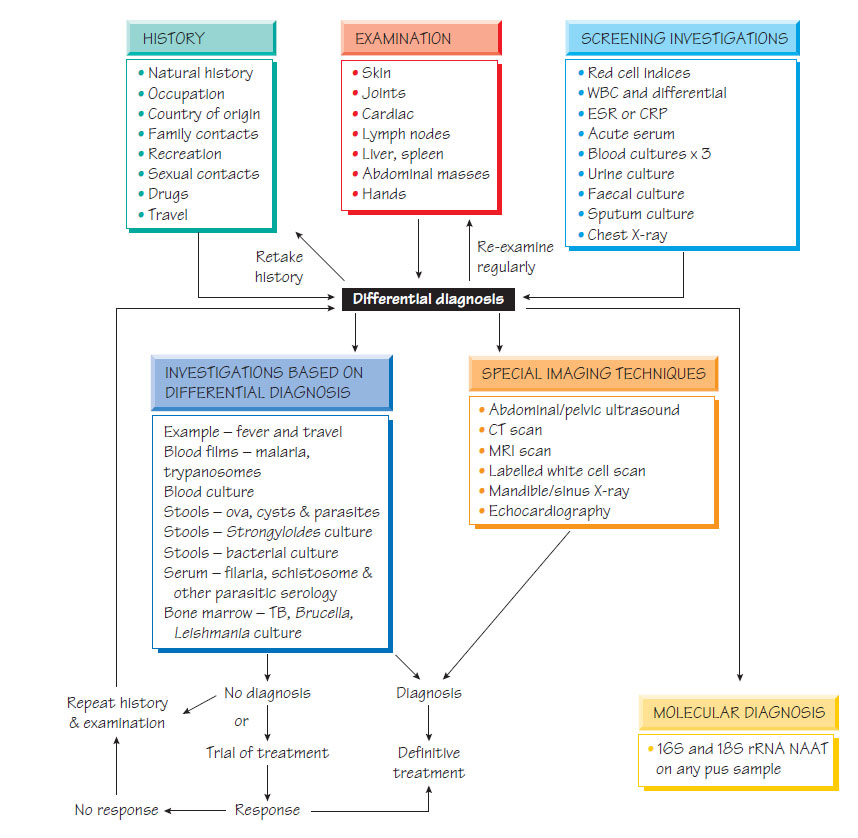

- Screening investigations, which are performed on all patients (see Figure).

- Investigations that depend on the results of history and physical examination.

- Further screening tests and special imaging techniques: ultrasound, CT, MRI, echocardiography and dental X-ray.

The results of the preliminary history and examination are taken together with the results of the primary investigations to plan the tests that will be performed in the second round. These investigations are chosen based on syndrome groups (e.g. fever, eosinophilia and tropical travel). If a diagnosis is not made, further imaging techniques may be required.

A diagnosis should be made before any antimicrobial therapy is commenced. In some infections, notably tuberculosis, which may be suspected but not proven, a trial of therapy may be considered. If this produces clinical improvement, a full course of chemotherapy may be initiated.

Septicaemia

Sources

- Skin sepsis:Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia may complicate skin infections.

- Normal flora: The organisms in the normal flora may become invasive (e.g. dental abscess, cholecystitis, appendicitis or diverticulitis).

- Following surgery: A wide range of organisms may be involved. This problem is particularly important in surgery that involves prosthetic devices (orthopaedic, cardiovascular, neurosurgical).

- Urinary tract: Enterobacteriaciae or enterococci (see Urinary and genital infections).

- Pneumonia: Streptococcus pneumoniae (see Respiratory tract infections).

- Meningitis: Neisseria meningitidis or S. pneumoniae.

- Patients are usually severely ill with fever, shock and, sometimes, depressed consciousness.

- If fever is absent, more common in children and elderly people, or shock has not yet developed, patients may present with confusion, drowsiness or being generally unwell.

- It is impossible to distinguish Gram-positive from Gramnegative shock.

- Some infections have characteristic signs (e.g. the purpura of N. meningitidis).

Diagnosis and Treatment

With the exception of suspected N. meningitidis infection, at least two specimens of peripheral blood should be taken for culture before therapy is commenced. Other investigations are directed towards finding the source of the sepsis, such as culture of urine, sputum, skin swabs and/or CSF. Chest and abdominal X-rays and abdominal ultrasound should be performed. Parenteral empirical antibiotics should be chosen based on the source of infection and the likely infecting organism.

This severe, usually bacteraemic, infection is caused by entry of pathogens through the placental bed or the cervix within 7 days of delivery. The organisms involved are either primary Pathogens introduced by medical manipulation (e.g. S. pyogenes) or elements of the normal flora (e.g. Bacteroides and coliforms) associated with retained products. Fever, back pain, offensive lochia or shock may be present and the infection may be complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Fever in the early puerperium should be investigated with blood and urine cultures and endocervical swabs. Empirical treatment with parenteral antibiotics, such as a third-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole or a combination for example of piperacillin plus tazobactam, should begin without delay. Retained products of conception should be removed. Intensive care support may be required.