Asexual Reproduction: Reproduction without Gametes

Asexual Reproduction:

Reproduction without

Gametes

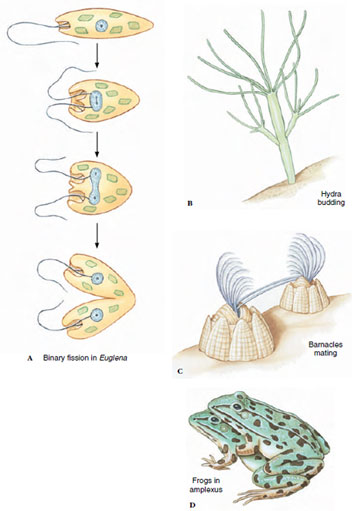

Asexual reproduction (see Figure 7-1A and B) is the production of individuals without gametes, that is, eggs or sperm. It includes a number of distinct processes to be described below, all without involving sex or a second parent. Offspring produced by asexual reproduction all have the same genotype (unless mutations occur) and are called clones.

Asexual reproduction appears in bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes and in many invertebrate phyla, such as cnidarians, bryozoans, annelids, echinoderms, and hemichordates. In animal phyla in which asexual reproduction occurs, most members also employ sexual reproduction. In these groups, asexual reproduction ensures rapid increase in numbers when differentiation of the organism has not advanced to the point of forming gametes. Asexual reproduction is absent among vertebrates (although some forms of parthenogenesis have been interpreted as asexual by some authors).

It would be a mistake to conclude that asexual reproduction is in any way a “defective” form of reproduction relegated to the minute forms of life that have not yet discovered the joys of sex. Given the facts of their abundance, that they have persisted on earth for 3.5 billion years, and that they form the roots of the food chain on which all higher forms depend, the single-celled asexual organisms are both resoundingly abundant and supremely important. For these forms the advantages of asexual reproduction are its rapidity (many bacteria divide every half hour) and simplicity (no germ cells to produce and no time and energy expended in finding a mate).

The basic forms of asexual reproduction are fission (binary and multiple), budding, gemmulation, and fragmentation.

Binary fission is common among bacteria and protozoa (Figure 7-1A). In binary fission the body of the parent divides by mitosis into two approximately equal parts, each of which grows into an individual similar to the parent. Binary fission may be lengthwise, as in flagellate protozoa, or transverse, as in ciliate protozoa. In multiple fission the nucleus divides repeatedly before division of the cytoplasm, producing many daughter cells simultaneously. Spore formation, called sporogony, is a form of multiple fission common among some parasitic protozoa, for example, malarial parasites.

Budding is an unequal division of an organism. The new individual arises as an outgrowth (bud) from the parent, develops organs like those of the parent, and then detaches itself. Budding occurs in several animal phyla and is especially prominent in cnidarians (Figure 7-1B).

Gemmulation is the formation of a new individual from an aggregation of cells surrounded by a resistant capsule, called a gemmule. In many freshwater sponges, gemmules develop in the fall and survive the winter in the dried or frozen body of the parent. In the spring, the enclosed cells become active, emerge from the capsule, and grow into a new sponge.

In fragmentation a multicellular animal breaks into two or more parts, with each fragment capable of becoming a complete individual. Many invertebrates can reproduce asexually by simply breaking into two parts and then regenerating the missing parts of the fragments.

|

| Figure 7-1 Asexual and sexual reproduction in animals. A, Binary fission in Euglena, a flagellate protozoan, results in two individuals. B, Budding, a simple form of asexual reproduction as shown in a hydra, a radiate animal. The buds eventually detach themselves and grow into fully formed individuals. C, Barnacles reproduce sexually, but are hermaphroditic, with each individual bearing both male and female organs. Each barnacle possesses a pair of enormously elongated penises—an obvious advantage to a sessile animal—that can be extended many times the length of the body to inseminate another barnacle some distance away. The partner may reciprocate with its own penises. D, Frogs, here in mating position (amplexus), represent bisexual reproduction, the most common form of sexual reproduction involving separate male and female individuals. |

Asexual reproduction (see Figure 7-1A and B) is the production of individuals without gametes, that is, eggs or sperm. It includes a number of distinct processes to be described below, all without involving sex or a second parent. Offspring produced by asexual reproduction all have the same genotype (unless mutations occur) and are called clones.

Asexual reproduction appears in bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes and in many invertebrate phyla, such as cnidarians, bryozoans, annelids, echinoderms, and hemichordates. In animal phyla in which asexual reproduction occurs, most members also employ sexual reproduction. In these groups, asexual reproduction ensures rapid increase in numbers when differentiation of the organism has not advanced to the point of forming gametes. Asexual reproduction is absent among vertebrates (although some forms of parthenogenesis have been interpreted as asexual by some authors).

It would be a mistake to conclude that asexual reproduction is in any way a “defective” form of reproduction relegated to the minute forms of life that have not yet discovered the joys of sex. Given the facts of their abundance, that they have persisted on earth for 3.5 billion years, and that they form the roots of the food chain on which all higher forms depend, the single-celled asexual organisms are both resoundingly abundant and supremely important. For these forms the advantages of asexual reproduction are its rapidity (many bacteria divide every half hour) and simplicity (no germ cells to produce and no time and energy expended in finding a mate).

The basic forms of asexual reproduction are fission (binary and multiple), budding, gemmulation, and fragmentation.

Binary fission is common among bacteria and protozoa (Figure 7-1A). In binary fission the body of the parent divides by mitosis into two approximately equal parts, each of which grows into an individual similar to the parent. Binary fission may be lengthwise, as in flagellate protozoa, or transverse, as in ciliate protozoa. In multiple fission the nucleus divides repeatedly before division of the cytoplasm, producing many daughter cells simultaneously. Spore formation, called sporogony, is a form of multiple fission common among some parasitic protozoa, for example, malarial parasites.

Budding is an unequal division of an organism. The new individual arises as an outgrowth (bud) from the parent, develops organs like those of the parent, and then detaches itself. Budding occurs in several animal phyla and is especially prominent in cnidarians (Figure 7-1B).

Gemmulation is the formation of a new individual from an aggregation of cells surrounded by a resistant capsule, called a gemmule. In many freshwater sponges, gemmules develop in the fall and survive the winter in the dried or frozen body of the parent. In the spring, the enclosed cells become active, emerge from the capsule, and grow into a new sponge.

In fragmentation a multicellular animal breaks into two or more parts, with each fragment capable of becoming a complete individual. Many invertebrates can reproduce asexually by simply breaking into two parts and then regenerating the missing parts of the fragments.