Nature of the Reproductive Process

Nature of the

Reproductive

Process

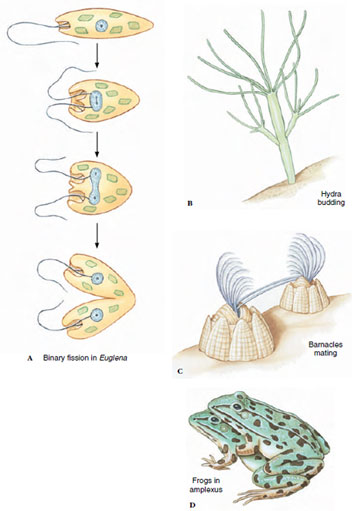

Two modes of reproduction are recognized:

asexual and sexual. In asexual

reproduction (Figure 7-1A and B) there

is only one parent and there are no

special reproductive organs or cells.

Each organism is capable of producing

genetically identical copies of itself as

soon as it becomes an adult. The production

of copies is marvelously simple,

direct, and typically rapid. Sexual reproduction (Figure 7-1C and D) as a

rule involves two parents, each of

which contributes special germ cells

(gametes or sex cells) that in union

(fertilization) develop into a new individual.

The zygote formed from this

union receives genetic material from

both parents, and the combination of

genes produces a genetically unique

individual, still bearing characteristics

of the species but also bearing traits

that make it different from its parents.

Sexual reproduction, by recombining

parental characters, tends to multiply

variations and makes possible a richer

and more diversified evolution.

Mechanisms for interchange of genes between individuals are more limited in organisms with only asexual reproduction. Of course, in asexual organisms that are haploid (bear only one set of genes), mutations are immediately expressed and evolution can proceed quickly. In sexual animals, on the other hand, a gene mutation is often not expressed immediately, since it may be masked by its normal partner on the homologous chromosome. (Homologous chromosomes, , are those that pair during meiosis and carry genes encoding the same characteristics.) There is only a remote chance that both members of a gene pair will mutate in the same way at the same moment.

|

| Figure 7-1 Asexual and sexual reproduction in animals. A, Binary fission in Euglena, a flagellate protozoan, results in two individuals. B, Budding, a simple form of asexual reproduction as shown in a hydra, a radiate animal. The buds eventually detach themselves and grow into fully formed individuals. C, Barnacles reproduce sexually, but are hermaphroditic, with each individual bearing both male and female organs. Each barnacle possesses a pair of enormously elongated penises—an obvious advantage to a sessile animal—that can be extended many times the length of the body to inseminate another barnacle some distance away. The partner may reciprocate with its own penises. D, Frogs, here in mating position (amplexus), represent bisexual reproduction, the most common form of sexual reproduction involving separate male and female individuals. |

Mechanisms for interchange of genes between individuals are more limited in organisms with only asexual reproduction. Of course, in asexual organisms that are haploid (bear only one set of genes), mutations are immediately expressed and evolution can proceed quickly. In sexual animals, on the other hand, a gene mutation is often not expressed immediately, since it may be masked by its normal partner on the homologous chromosome. (Homologous chromosomes, , are those that pair during meiosis and carry genes encoding the same characteristics.) There is only a remote chance that both members of a gene pair will mutate in the same way at the same moment.