Hormones of Human Pregnancy and Birth

Hormones of Human

Pregnancy and Birth

If fertilization occurs, it normally does

so in the first third of the uterine tube

(ampulla), and the zygote travels

from here to the uterus, dividing

by mitosis to form a blastocyst (see

Principles of Development) by the time it

reaches the uterus. The developing

blastocyst will contact the uterine surface

after about 6 days and bury itself

in the endometrium. This process is

called implantation. Growth of the

embryo continues, producing a spherically

shaped trophoblast. This embryonic

stage contains three distinct tissue

layers, the amnion, chorion, and

embryo proper, the inner cell mass

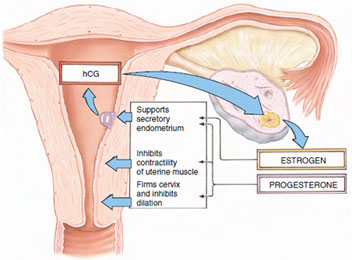

(Figure 8-23). The chorion becomes the source of human chorionic

gonadotropin (hCG), which

appears in the bloodstream soon after

implantation. hCG stimulates the corpus

luteum to synthesize and release

both estrogen and progesterone (Figure

7-16).

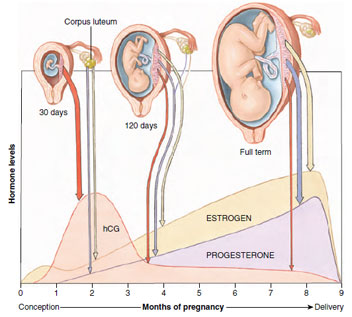

The point of attachment between trophoblast and uterus becomes the placenta (evolution and development of the placenta is described in See: Principles of Development). Besides serving as a medium for the transfer of materials between maternal and fetal bloodstreams, the placenta also serves as an endocrine gland. The placenta continues to secrete hCG and also produces estrogen (mainly estriol) and progesterone. After about the third month of pregnancy, the corpus luteum degenerates, but by then the placenta itself is the main source of both progesterone and estrogen (Figure 7-17).

Preparation of the mammary

glands for secretion of milk requires

two additional hormones, prolactin

(PRL) and human placental lactogen

(hPL) (or human chorionic

somatomammotropin). PRL is produced

by the anterior pituitary, but in

nonpregnant women its secretion is

inhibited. During pregnancy, elevated

levels of progesterone and estrogen

depress the inhibitory signal, and PRL

begins to appear in the blood. PRL, in

combination with hPL, prepare the

mammary glands for secretion. hPL,

together with maternal growth hormone,

also stimulates an increase in

available nutrients in the mother, so

that more are provided to the developing

embryo. Later the placenta

begins to synthesize a peptide hormone

called relaxin; this hormone

allows some expansion of the pelvis

by increasing the flexibility of the

pubic symphysis, and also dilates the

cervix in preparation for delivery.

Birth, or parturition, begins with a series of strong, rhythmic contractions of the uterine musculature, called labor. The exact signal that triggers birth is not fully understood in humans, but several important factors have been identified in other mammals. Just before birth, secretion of estrogen, which stimulates uterine contractions, rises sharply, while the level of progesterone, which inhibits uterine contractions, declines (Figure 7-17). This removes the “progesterone block” that keeps the uterus quiescent throughout pregnancy. Prostaglandins, a large group of hormones (long-chain fatty acid derivatives), also increase at this time, making the uterus more “irritable” (See: Chemical Coordination, for more on prostaglandins). Finally, stretching of the uterus sets in motion neural reflexes that stimulate secretion of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary. Oxytocin also stimulates uterine smooth muscle, leading to stronger and more frequent labor contractions.

Given the intricacy of pregnancy it may seem remarkable that healthy babies are ever born! In fact we are the lucky survivors of pregnancy, for miscarriages are quite common and serve as a mechanism to reject prenatal abnormalities such as chromosomal damage and other genetic errors, exposure to drugs or toxins, immune irregularities, or improper hormonal priming of the uterus. Modern hormonal tests show that about 30 percent of fertile zygotes are spontaneously aborted before or right after implantation; such miscarriages are unknown to the motheror are expressed as a slightly late menstrual period.Another 20 percent of established pregnancies end in miscarriage (those known to the mother), giving a spontaneous abortion rate of about 50 percent.

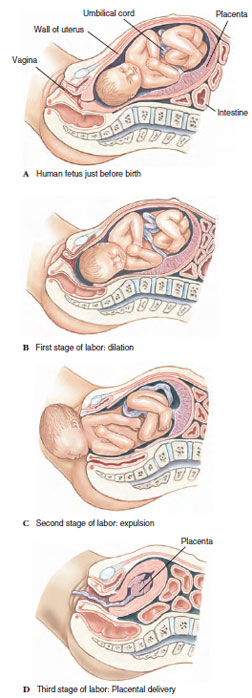

Childbirth occurs in three stages. In the first stage the neck (cervix), or opening of the uterus into the vagina, is enlarged by pressure from the baby in its bag of amniotic fluid, which may be ruptured at this time (Figure 7-18B). In the second stage, the baby is forced out of the uterus and through the vagina to the outside (Figure 7-18C). In the third stage, the placenta, or afterbirth, is expelled from the mother’s body, usually within 10 minutes after the baby is born (Figure 7-18D).

After birth, secretion of milk is triggered when the infant sucks on its mother’s nipple. This leads to a reflex release of oxytocin from the pituitary; when oxytocin reaches the mammary glands it causes contraction of smooth muscles lining ducts and sinuses of the mammary glands and ejection of milk. Suckling also stimulates release of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland, which stimulates continued production of milk by the mammary glands.

|

| Figure 7-16 The multiple roles of progesterone and estrogen in normal human pregnancy. After implantation of an embryo in the uterus, the trophoblast (the future embryo and placenta) secretes human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) which maintains the corpus luteum until the placenta, at about the seventh week of pregnancy, begins producing the sex hormones progesterone and estrogen. |

The point of attachment between trophoblast and uterus becomes the placenta (evolution and development of the placenta is described in See: Principles of Development). Besides serving as a medium for the transfer of materials between maternal and fetal bloodstreams, the placenta also serves as an endocrine gland. The placenta continues to secrete hCG and also produces estrogen (mainly estriol) and progesterone. After about the third month of pregnancy, the corpus luteum degenerates, but by then the placenta itself is the main source of both progesterone and estrogen (Figure 7-17).

|

| Figure 7-17 Hormone levels released from the corpus luteum and placenta during pregnancy. The width of the arrows suggests the relative amounts of hormone released; hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) is produced solely by the placenta. Synthesis of progesterone and estrogen shifts during pregnancy from the corpus luteum to the placenta. |

Birth, or parturition, begins with a series of strong, rhythmic contractions of the uterine musculature, called labor. The exact signal that triggers birth is not fully understood in humans, but several important factors have been identified in other mammals. Just before birth, secretion of estrogen, which stimulates uterine contractions, rises sharply, while the level of progesterone, which inhibits uterine contractions, declines (Figure 7-17). This removes the “progesterone block” that keeps the uterus quiescent throughout pregnancy. Prostaglandins, a large group of hormones (long-chain fatty acid derivatives), also increase at this time, making the uterus more “irritable” (See: Chemical Coordination, for more on prostaglandins). Finally, stretching of the uterus sets in motion neural reflexes that stimulate secretion of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary. Oxytocin also stimulates uterine smooth muscle, leading to stronger and more frequent labor contractions.

|

| Figure 7-18 Birth, or parturition, in humans. |

Given the intricacy of pregnancy it may seem remarkable that healthy babies are ever born! In fact we are the lucky survivors of pregnancy, for miscarriages are quite common and serve as a mechanism to reject prenatal abnormalities such as chromosomal damage and other genetic errors, exposure to drugs or toxins, immune irregularities, or improper hormonal priming of the uterus. Modern hormonal tests show that about 30 percent of fertile zygotes are spontaneously aborted before or right after implantation; such miscarriages are unknown to the motheror are expressed as a slightly late menstrual period.Another 20 percent of established pregnancies end in miscarriage (those known to the mother), giving a spontaneous abortion rate of about 50 percent.

Childbirth occurs in three stages. In the first stage the neck (cervix), or opening of the uterus into the vagina, is enlarged by pressure from the baby in its bag of amniotic fluid, which may be ruptured at this time (Figure 7-18B). In the second stage, the baby is forced out of the uterus and through the vagina to the outside (Figure 7-18C). In the third stage, the placenta, or afterbirth, is expelled from the mother’s body, usually within 10 minutes after the baby is born (Figure 7-18D).

After birth, secretion of milk is triggered when the infant sucks on its mother’s nipple. This leads to a reflex release of oxytocin from the pituitary; when oxytocin reaches the mammary glands it causes contraction of smooth muscles lining ducts and sinuses of the mammary glands and ejection of milk. Suckling also stimulates release of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland, which stimulates continued production of milk by the mammary glands.