Sex Determination

Sex Determination

At first gonads are sexually indifferent. In normal human males, a “maledetermining gene” on the Y chromosome called SRY (sex-determining region Y) organizes the developing gonad into a testis instead of an ovary. Once formed, the testis secretes the steroid testosterone. This hormone, and its metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), masculinizes the fetus, causing the differentiation of penis, scrotum, and the male ducts and glands. It also destroys the incipient breast primordia, but leaves behind the nipples as a reminder of the indifferent ground plan from which both sexes develop. Testosterone is also responsible for the masculinization of the brain, but it does so indirectly. Surprisingly, testosterone is enzymatically converted to estrogen in the brain, and it is estrogen that determines the organization of the brain for male-typical behavior.

Biologists have often stated that in mammals the indifferent gonad has an inherent tendency to become an ovary. In rabbits, for example, removal of the fetal gonads before they have differentiated will invariably produce a female with uterine tubes, uterus, and vagina, even if the rabbit is a genetic male. Localization in 1994 of a region on the X chromosome named DDS (dosagesensitive sex reversal) or SRVX (sex-reversing X), which promotes ovary formation, has challenged this view. In addition, the presence of such a region may help to explain feminization in some XY males. It is clear, however, that absence of testosterone in a genetic female embryo promotes development of female sexual organs: vagina, clitoris, and uterus. The developing female brain does require special protection from the effects of estrogen because, as mentioned above, estrogen causes masculinization of the brain. In rats, a blood protein (alpha-fetoprotein) binds to estrogen and keeps the hormone from reaching the brain. This does not appear to be the case in humans, however, and even though circulating fetal estrogen levels can be quite high, the female developing brain does not become masculinized. One possible explanation for the lack of masculinization of the developing human female brain is that the level of brain estrogen receptors is low, and therefore, high levels of circulating estrogen would not have an effect.

For every structure in the reproductive system of the male or female, there is a homologous structure in the other.This happens because during early development male and female characteristics begin to differentiate from the embryonic genital ridge and two duct systems that at first are identical in both sexes. Under the influence of the sex hormones,the genital ridge develops into the testes of the male and the ovaries of the female. One duct system (mesonephric or Wolffian) becomes ducts of the testes in the male and a vestigial structure adjacent to the ovaries in the female.The other duct (paramesonephric or Müllerian) develops into the uterine tubes, uterus, and vagina of the female and into the small, vestigial appendix of the testes in the male. Similarly, the clitoris and labia of the female are homologous to the penis and scrotum of the male, since they develop from the same embryonic structures.

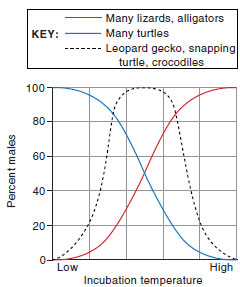

The genetics of sex determination are treated in Principles of Genetics:A Review. Sex determination is strictly chromosomal in mammals, birds, amphibians, many reptiles, and probably most fishes. However, many fishes and reptiles lack sex chromosomes altogether; in these groups, gender is determined by nongenetic factors such as temperature or behavior. In crocodilians, many turtles, and some lizards the incubation temperature of the nest determines the sex ratio by some as yet unknown sexdetermining mechanism. Alligator eggs, for example, incubated at low temperature all become females; those incubated at higher temperature all become males (Figure 7-6). Sex determination of many fishes is behavior dependent. Most of these species are hermaphroditic, possessing both male and female gonads. Sensory stimuli from the animal’s social environment determine whether it will be male or female.

At first gonads are sexually indifferent. In normal human males, a “maledetermining gene” on the Y chromosome called SRY (sex-determining region Y) organizes the developing gonad into a testis instead of an ovary. Once formed, the testis secretes the steroid testosterone. This hormone, and its metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), masculinizes the fetus, causing the differentiation of penis, scrotum, and the male ducts and glands. It also destroys the incipient breast primordia, but leaves behind the nipples as a reminder of the indifferent ground plan from which both sexes develop. Testosterone is also responsible for the masculinization of the brain, but it does so indirectly. Surprisingly, testosterone is enzymatically converted to estrogen in the brain, and it is estrogen that determines the organization of the brain for male-typical behavior.

Biologists have often stated that in mammals the indifferent gonad has an inherent tendency to become an ovary. In rabbits, for example, removal of the fetal gonads before they have differentiated will invariably produce a female with uterine tubes, uterus, and vagina, even if the rabbit is a genetic male. Localization in 1994 of a region on the X chromosome named DDS (dosagesensitive sex reversal) or SRVX (sex-reversing X), which promotes ovary formation, has challenged this view. In addition, the presence of such a region may help to explain feminization in some XY males. It is clear, however, that absence of testosterone in a genetic female embryo promotes development of female sexual organs: vagina, clitoris, and uterus. The developing female brain does require special protection from the effects of estrogen because, as mentioned above, estrogen causes masculinization of the brain. In rats, a blood protein (alpha-fetoprotein) binds to estrogen and keeps the hormone from reaching the brain. This does not appear to be the case in humans, however, and even though circulating fetal estrogen levels can be quite high, the female developing brain does not become masculinized. One possible explanation for the lack of masculinization of the developing human female brain is that the level of brain estrogen receptors is low, and therefore, high levels of circulating estrogen would not have an effect.

|

| Figure 7-6 Temperature-dependent sex determination. In many reptiles that lack sex chromosomes incubation temperature of the nest determines gender. The graph shows that embryos of many turtles develop into males at low temperature, whereas embryos of many lizards and alligators become males at high temperatures. Embryos of crocodiles become males at intermediate temperatures, and become females at higher or lower temperatures. |

For every structure in the reproductive system of the male or female, there is a homologous structure in the other.This happens because during early development male and female characteristics begin to differentiate from the embryonic genital ridge and two duct systems that at first are identical in both sexes. Under the influence of the sex hormones,the genital ridge develops into the testes of the male and the ovaries of the female. One duct system (mesonephric or Wolffian) becomes ducts of the testes in the male and a vestigial structure adjacent to the ovaries in the female.The other duct (paramesonephric or Müllerian) develops into the uterine tubes, uterus, and vagina of the female and into the small, vestigial appendix of the testes in the male. Similarly, the clitoris and labia of the female are homologous to the penis and scrotum of the male, since they develop from the same embryonic structures.

The genetics of sex determination are treated in Principles of Genetics:A Review. Sex determination is strictly chromosomal in mammals, birds, amphibians, many reptiles, and probably most fishes. However, many fishes and reptiles lack sex chromosomes altogether; in these groups, gender is determined by nongenetic factors such as temperature or behavior. In crocodilians, many turtles, and some lizards the incubation temperature of the nest determines the sex ratio by some as yet unknown sexdetermining mechanism. Alligator eggs, for example, incubated at low temperature all become females; those incubated at higher temperature all become males (Figure 7-6). Sex determination of many fishes is behavior dependent. Most of these species are hermaphroditic, possessing both male and female gonads. Sensory stimuli from the animal’s social environment determine whether it will be male or female.