Bisexual Reproduction

Bisexual Reproduction

Bisexual reproduction is the production

of offspring formed by the union of

gametes from two genetically different

parents (Figures 7-1C and D, and 7-2).

The offspring will thus have a new

genotype different from either of the

parents. The individuals sharing parenthood

are characteristically of different sexes, male and female (there are

exceptions among sexually reproducing

organisms, such as bacteria and

some protozoa in which sexes are

lacking). Each has its own reproductive

system and produces only one

kind of germ cell, spermatozoon or

ovum, but never both. Nearly all vertebrates

and many invertebrates have

separate sexes, and such a condition is

called dioecious (Gr. di-, two, + oikos, house). An exception to this is

found in individual animals that have

both male and female reproductive

organs, a condition which is called monoecious (Gr. monos, single, + oikos, house). These animals are called hermaphrodites (from a combination

of the names of the Greek god Hermes

and goddess Aphrodite) and this form

of reproduction will be described in

the next section.

The distinction between male and female is based, not on any differences in parental size or appearance, but on the size and mobility of the gametes they produce. The ovum (egg) is produced by the female. Ova are large (because of stored yolk to sustain early development), nonmotile, and produced in relatively small numbers. The spermatozoon (sperm) is produced by the male. Sperm are small, motile, and produced in enormous numbers. Each is a stripped-down package of highly condensed genetic material designed for the single purpose of reaching and fertilizing an egg.

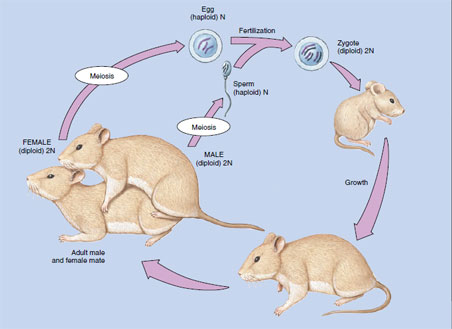

There is another crucial event that distinguishes sexual from asexual reproduction: meiosis, a distinctive type of gamete-producing nuclear division). Meiosis differs from ordinary cell division (mitosis) in being a double division. The chromosomes split once, but the cell divides twice, producing four cells, each with half the original number of chromosomes (the haploid number). Meiosis is followed by fertilization in which two haploid gametes are combined to restore the normal (diploid) chromosomal number of the species.

The new cell (zygote), which now begins to divide by mitosis, has equal numbers of chromosomes from each parent and accordingly is different from each. It is a unique individual bearing a recombination of parental characteristics. Genetic recombination is the great strength of sexual reproduction that keeps feeding new genetic combinations into the population.

Many unicellular organisms reproduce both sexually and asexually. When sexual reproduction does occur, it may or may not involve male and female gametes. Sometimes two mature sexual parents merely join together to exchange nuclear material or merge cytoplasm (conjugation, Protozoan Groups). Distinct sexes do not exist in these cases.

The male-female distinction is more clearly evident in most animals. Organs that produce germ cells are called gonads. The gonad that produces sperm is a testis and that which forms eggs is an ovary . Gonads represent the primary sex organs, the only sex organs found in certain groups of animals. Most metazoa, however, have various accessory sex organs (such as penis, vagina, uterine tubes, and uterus) that transfer and receive germ cells. In the primary sex organs the germ cells undergo many complicated changes during their development, the details of which are described later.

|

| Figure 7-2 A sexual life cycle. The life cycle begins with haploid germ cells, formed by meiosis, combining to form a diploid zygote, which grows by mitosis to an adult. Most of the life cycle is spent as a diploid organism. |

The distinction between male and female is based, not on any differences in parental size or appearance, but on the size and mobility of the gametes they produce. The ovum (egg) is produced by the female. Ova are large (because of stored yolk to sustain early development), nonmotile, and produced in relatively small numbers. The spermatozoon (sperm) is produced by the male. Sperm are small, motile, and produced in enormous numbers. Each is a stripped-down package of highly condensed genetic material designed for the single purpose of reaching and fertilizing an egg.

There is another crucial event that distinguishes sexual from asexual reproduction: meiosis, a distinctive type of gamete-producing nuclear division). Meiosis differs from ordinary cell division (mitosis) in being a double division. The chromosomes split once, but the cell divides twice, producing four cells, each with half the original number of chromosomes (the haploid number). Meiosis is followed by fertilization in which two haploid gametes are combined to restore the normal (diploid) chromosomal number of the species.

The new cell (zygote), which now begins to divide by mitosis, has equal numbers of chromosomes from each parent and accordingly is different from each. It is a unique individual bearing a recombination of parental characteristics. Genetic recombination is the great strength of sexual reproduction that keeps feeding new genetic combinations into the population.

Many unicellular organisms reproduce both sexually and asexually. When sexual reproduction does occur, it may or may not involve male and female gametes. Sometimes two mature sexual parents merely join together to exchange nuclear material or merge cytoplasm (conjugation, Protozoan Groups). Distinct sexes do not exist in these cases.

The male-female distinction is more clearly evident in most animals. Organs that produce germ cells are called gonads. The gonad that produces sperm is a testis and that which forms eggs is an ovary . Gonads represent the primary sex organs, the only sex organs found in certain groups of animals. Most metazoa, however, have various accessory sex organs (such as penis, vagina, uterine tubes, and uterus) that transfer and receive germ cells. In the primary sex organs the germ cells undergo many complicated changes during their development, the details of which are described later.