Why Do So Many Animals Reproduce Sexually Rather Than Asexually?

Why Do So Many Animals

Reproduce Sexually Rather

Than Asexually?

Because sexual reproduction is so

nearly universal among animals, it

might be inferred to be highly advantageous.

Yet it is easier to list disadvantages

to sex than advantages. Sexual reproduction is complicated, requires

more time, and uses much more energy

than asexual reproduction. Mating

partners must come together and coordinate

their activities to produce

young. Many biologists believe that an

even more troublesome problem is the

“cost of meiosis.” A female that reproduces

asexually passes all of her genes

to her offspring. But when she reproduces

sexually the genome is divided

during meiosis and only half her genes

flow to the next generation. Another

cost is wastage in production of males,

many of which fail to reproduce and

thus consume resources that could be

applied to production of females.

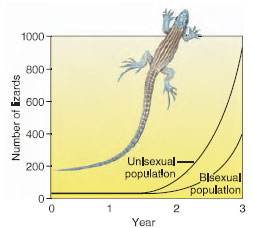

Whiptail lizards of the American southwest

offer a fascinating example of the

potential advantage of parthenogenesis.

When unisexual and bisexual

species of the same genus are reared

under similar conditions in the laboratory,

the population of the unisexual

species grows more quickly because

all unisexual lizards (all females)

deposit eggs, whereas only 50% of the

bisexual lizards do so (Figure 7-4).

Variety may make sexual reproduction a winning strategy for the unstable environment, but some biologists believe that for many vertebrates sexual reproduction is unnecessary and may even be maladaptive. In animals in which most of the young survive to reproductive age (humans, for example), there is no demand for novel recombinations to cope with changing habitats. One offspring appears as successful as the next in each habitat. Significantly, parthenogenesis has evolved in several species of fish and in a few amphibians and reptiles. Such species are exclusively parthenogenetic, suggesting that where it has been possible to overcome the numerous constraints to making the transition, bisexual reproduction loses out.

Clearly, the costs of sexual reproduction are substantial. How are they offset? Biologists have disputed this question for years without producing an answer that satisfies everyone. Many biologists believe that sexual reproduction, with its breakup and recombination of genomes, keeps producing novel genotypes that in times of environmental change may survive and reproduce, whereas most others die. Variability, advocates of this viewpoint argue, is sexual reproduction’s trump card.

But is variability worth the biological costs of sexual reproduction? The underlying problem keeps coming back: asexual organisms, because they can have more offspring in a given time, appear to be more fit in Darwinian terms. And yet most metazoan animals are determinedly committed to sexuality. Considerable evidence suggests that asexual reproduction is most successful in colonizing new environments. When habitats are empty what matters most is rapid reproduction; variability matters little. But as habitats become more crowded, competition between species for resources increases. Selection becomes more intense, and genetic variability—new genotypes produced by recombination in sexual reproduction—furnishes the diversity that permits a population to resist extinction. Therefore, on a geological timescale, asexual lineages, because of the lack of genetic flexibility, may be more prone to extinction than sexual lineages. Sexual reproduction is therefore favored by species selection. There are many invertebrates that use both sexual and asexual reproduction, thus enjoying the advantages each has to offer.

|

| Figure 7-4 Comparison of the growth of a population of unisexual whiptail lizards with a population of bisexual lizards. Because all individuals of the unisexual population are females, all produce eggs, whereas only half the bisexual population are egg-producing females. By the end of the third year the unisexual lizards are more than twice as numerous as the bisexual ones. |

Variety may make sexual reproduction a winning strategy for the unstable environment, but some biologists believe that for many vertebrates sexual reproduction is unnecessary and may even be maladaptive. In animals in which most of the young survive to reproductive age (humans, for example), there is no demand for novel recombinations to cope with changing habitats. One offspring appears as successful as the next in each habitat. Significantly, parthenogenesis has evolved in several species of fish and in a few amphibians and reptiles. Such species are exclusively parthenogenetic, suggesting that where it has been possible to overcome the numerous constraints to making the transition, bisexual reproduction loses out.

Clearly, the costs of sexual reproduction are substantial. How are they offset? Biologists have disputed this question for years without producing an answer that satisfies everyone. Many biologists believe that sexual reproduction, with its breakup and recombination of genomes, keeps producing novel genotypes that in times of environmental change may survive and reproduce, whereas most others die. Variability, advocates of this viewpoint argue, is sexual reproduction’s trump card.

But is variability worth the biological costs of sexual reproduction? The underlying problem keeps coming back: asexual organisms, because they can have more offspring in a given time, appear to be more fit in Darwinian terms. And yet most metazoan animals are determinedly committed to sexuality. Considerable evidence suggests that asexual reproduction is most successful in colonizing new environments. When habitats are empty what matters most is rapid reproduction; variability matters little. But as habitats become more crowded, competition between species for resources increases. Selection becomes more intense, and genetic variability—new genotypes produced by recombination in sexual reproduction—furnishes the diversity that permits a population to resist extinction. Therefore, on a geological timescale, asexual lineages, because of the lack of genetic flexibility, may be more prone to extinction than sexual lineages. Sexual reproduction is therefore favored by species selection. There are many invertebrates that use both sexual and asexual reproduction, thus enjoying the advantages each has to offer.