Vertebrate Reproductive Systems

Vertebrate Reproductive

Systems

In vertebrates the reproductive and excretory systems are together called a urogenital system because of their close anatomical connection, especially in males. This association is very striking during embryonic development. In male fishes and amphibians the duct that drains the kidney (mesonephric duct or Wolffian duct) also serves as a sperm duct. In male reptiles, birds, and mammals in which the kidney develops its own independent duct (ureter) to carry away waste, the old mesonephric duct becomes exclusively a sperm duct or vas deferens. In all these forms, with the exception of most mammals, the ducts open into a cloaca (derived, appropriately, from the Latin meaning “sewer”), a common chamber into which intestinal, reproductive, and excretory canals empty. Almost all placental mammals have no cloaca; instead the urogenital system has its own opening separate from the anal opening. The uterine duct or oviduct of the female is an independent duct that does, however, open into the cloaca in forms having a cloaca.

Male Reproductive System

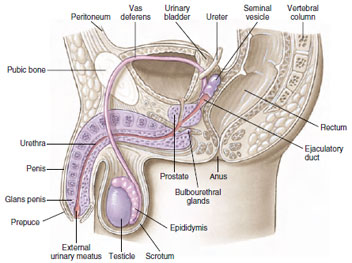

The male reproductive system of vertebrates,

such as that of human males

(Figure 7-12) includes testes, vasa

efferentia, vas deferens, accessory

glands, and (in some birds and reptiles,

and all mammals) a penis.

The paired testes are the sites of sperm production. Each testis is composed of numerous seminiferous tubules, in which the sperm develop (Figure 7-8). The sperm are surrounded by sustentacular cells (or Sertoli cells), which nourish the developing sperm. Between the tubules are interstitial cells, which produce the male sex hormone (testosterone). In most mammals the two testes are housed permanently in a sac-like scrotum suspended outside the abdominal cavity, or the testes descend into the scrotum during the breeding season. This odd and seemingly insecure arrangement provides an environment of slightly lower temperature, since in most mammals (including humans) sperm apparently do not form at temperatures maintained within the body. In marine mammals and all other vertebrates the testes are positioned permanently within the abdomen.

The sperm travel from the seminiferous tubules to the vasa efferentia, small tubes passing to a coiled epididymis (one for each testis), where final sperm maturation takes place, and then to a vas deferens, the ejaculatory duct (Figure 7-8). In mammals the vas deferens joins the urethra, a duct that serves to carry both sperm and urinary products through the penis, or external intromittent organ.

Most aquatic vertebrates have no need for a penis, since sperm and eggs are liberated into the water in close proximity to each other.However, in terrestrial (and some aquatic) vertebrates that bear their young alive or enclose the egg within a shell, sperm must be transferred to the female. In most birds, this is a rather haphazard process of simply presenting cloaca to cloaca. Only reptiles and mammals have a true penis. In mammals the normally flaccid organ becomes erect when engorged with blood.Many other mammals possess a bone in the penis (baculum), which presumably helps with rigidity.

In most mammals three sets of accessory glands open into the reproductive channels: a pair of seminal vesicles, a single prostate gland, and the pair of bulbourethral glands (Figure 7-12). Fluid secreted by these glands furnishes food to the sperm, lubricates the passageways for sperm, and counteracts the acidity of the urine so that the sperm are not harmed.

Female Reproductive System

The ovaries of female vertebrates produce

both ova and female sex hormones

(estrogens and progesterone).

In all jawed vertebrates, mature ova

from each ovary enter the funnel-like

opening of a uterine tube or oviduct,

which typically has a fringed margin

that envelops the ovary at the time of

ovulation. The terminal end of the

uterine tube is unspecialized in most

fishes and amphibians, but in cartilaginous

fishes, reptiles, and birds that

produce a large, shelled egg, special

regions have developed for production

of albumin and shell. In amniotes

(reptiles, birds, and mammals; see

Amniotes and the Amniotic Egg) the terminal portion of the uterine

tube is expanded into a muscular

uterus in which shelled eggs are held

before laying or in which embryos

complete their development. In placental

mammals, the walls of the uterus establish a close vascular association

with the embryonic membranes

through a placenta.

The paired ovaries of the human female (Figure 7-13), slightly smaller than the male testes, contain many thousands of oocytes. Each oocyte develops within a follicle that enlarges and finally ruptures to release a secondary oocyte (Figure 7-10). During a woman’s fertile years, except following fertilization, approximately 13 oocytes mature each year, and usually the ovaries alternate in releasing oocytes. Because a woman is fertile for only about 30 years, of the approximately 400,000 primary oocytes in her ovaries at birth, only 300 to 400 have a chance to reach maturity; the others degenerate and are absorbed.

The uterine tubes, or oviducts, are lined with cilia for propelling the egg in its course. The two ducts open into the upper corners of the uterus, or womb, which is specialized for housing the embryo during the 9 months of its intrauterine existence. It is provided with thick muscular walls, many blood vessels, and a specialized lining: the endometrium. The uterus varies among different mammals, and in many it is designed to hold more than one developing embryo. Ancestrally it was paired but is fused in many eutherian mammals.

The vagina is a muscular tube adapted for receiving the male’s penis and for serving as birth canal during expulsion of a fetus from the uterus. Where vagina and uterus meet, the uterus projects down into the vagina to form a cervix.

The external genitalia of human females, or vulva, include folds of skin, the labia majora and labia minora, and a small erectile organ, the clitoris (the female homolog of the glans penis of males). The opening into the vagina is often reduced in size in the virgin state by a membrane, the hymen, although in sexually active females, this membrane may be much reduced in extent.

In vertebrates the reproductive and excretory systems are together called a urogenital system because of their close anatomical connection, especially in males. This association is very striking during embryonic development. In male fishes and amphibians the duct that drains the kidney (mesonephric duct or Wolffian duct) also serves as a sperm duct. In male reptiles, birds, and mammals in which the kidney develops its own independent duct (ureter) to carry away waste, the old mesonephric duct becomes exclusively a sperm duct or vas deferens. In all these forms, with the exception of most mammals, the ducts open into a cloaca (derived, appropriately, from the Latin meaning “sewer”), a common chamber into which intestinal, reproductive, and excretory canals empty. Almost all placental mammals have no cloaca; instead the urogenital system has its own opening separate from the anal opening. The uterine duct or oviduct of the female is an independent duct that does, however, open into the cloaca in forms having a cloaca.

Male Reproductive System

|

| Figure 7-12 Human male reproductive system showing the reproductive structures in sagittal view. |

The paired testes are the sites of sperm production. Each testis is composed of numerous seminiferous tubules, in which the sperm develop (Figure 7-8). The sperm are surrounded by sustentacular cells (or Sertoli cells), which nourish the developing sperm. Between the tubules are interstitial cells, which produce the male sex hormone (testosterone). In most mammals the two testes are housed permanently in a sac-like scrotum suspended outside the abdominal cavity, or the testes descend into the scrotum during the breeding season. This odd and seemingly insecure arrangement provides an environment of slightly lower temperature, since in most mammals (including humans) sperm apparently do not form at temperatures maintained within the body. In marine mammals and all other vertebrates the testes are positioned permanently within the abdomen.

The sperm travel from the seminiferous tubules to the vasa efferentia, small tubes passing to a coiled epididymis (one for each testis), where final sperm maturation takes place, and then to a vas deferens, the ejaculatory duct (Figure 7-8). In mammals the vas deferens joins the urethra, a duct that serves to carry both sperm and urinary products through the penis, or external intromittent organ.

Most aquatic vertebrates have no need for a penis, since sperm and eggs are liberated into the water in close proximity to each other.However, in terrestrial (and some aquatic) vertebrates that bear their young alive or enclose the egg within a shell, sperm must be transferred to the female. In most birds, this is a rather haphazard process of simply presenting cloaca to cloaca. Only reptiles and mammals have a true penis. In mammals the normally flaccid organ becomes erect when engorged with blood.Many other mammals possess a bone in the penis (baculum), which presumably helps with rigidity.

In most mammals three sets of accessory glands open into the reproductive channels: a pair of seminal vesicles, a single prostate gland, and the pair of bulbourethral glands (Figure 7-12). Fluid secreted by these glands furnishes food to the sperm, lubricates the passageways for sperm, and counteracts the acidity of the urine so that the sperm are not harmed.

Female Reproductive System

|

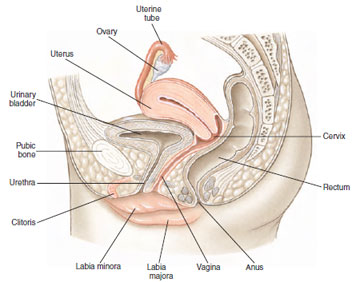

| Figure 7-13 Human female reproductive system showing the pelvis in sagittal section. |

The paired ovaries of the human female (Figure 7-13), slightly smaller than the male testes, contain many thousands of oocytes. Each oocyte develops within a follicle that enlarges and finally ruptures to release a secondary oocyte (Figure 7-10). During a woman’s fertile years, except following fertilization, approximately 13 oocytes mature each year, and usually the ovaries alternate in releasing oocytes. Because a woman is fertile for only about 30 years, of the approximately 400,000 primary oocytes in her ovaries at birth, only 300 to 400 have a chance to reach maturity; the others degenerate and are absorbed.

The uterine tubes, or oviducts, are lined with cilia for propelling the egg in its course. The two ducts open into the upper corners of the uterus, or womb, which is specialized for housing the embryo during the 9 months of its intrauterine existence. It is provided with thick muscular walls, many blood vessels, and a specialized lining: the endometrium. The uterus varies among different mammals, and in many it is designed to hold more than one developing embryo. Ancestrally it was paired but is fused in many eutherian mammals.

The vagina is a muscular tube adapted for receiving the male’s penis and for serving as birth canal during expulsion of a fetus from the uterus. Where vagina and uterus meet, the uterus projects down into the vagina to form a cervix.

The external genitalia of human females, or vulva, include folds of skin, the labia majora and labia minora, and a small erectile organ, the clitoris (the female homolog of the glans penis of males). The opening into the vagina is often reduced in size in the virgin state by a membrane, the hymen, although in sexually active females, this membrane may be much reduced in extent.