Early Concepts: Preformation Versus Epigenesis

Early Concepts:

Preformation Versus

Epigenesis

Early scientists and laypeople alike

speculated at length about the mystery

of development long before the

process was submitted to modern techniques

of biochemistry, molecular biology,

tissue culture, and electron

microscopy. An early and persistent

idea was that young animals were preformed

in eggs and that development

was simply a matter of unfolding what

was already there. Some claimed they

could actually see a miniature of the

adult in the egg or sperm (Figure 8-1).

Even the more cautious argued that all

parts of the embryo were in the egg,

needing only to unfold, but so small

and transparent they could not be

seen. The concept of preformation was strongly advocated by most

seventeenth- and eighteenth-century

naturalist-philosophers.

In 1759 German embryologist Kaspar Friedrich Wolff clearly showed that in the earliest developmental stages of the chick, there was no preformed individual, only undifferentiated granular material that became arranged into layers. These layers continued to thicken in some areas, to become thinner in others, to fold, and to segment, until the body of the embryo appeared. Wolff called this process epigenesis (“origin upon or after”), an idea that a fertilized egg contains building material only, somehow assembled by an unknown directing force. Current ideas of development are essentially epigenetic in concept, although we know far more about what directs growth and differentiation.

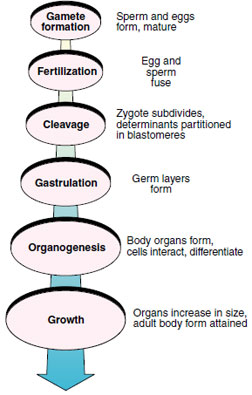

Development describes the progressive

changes in an individual from

its beginning to maturity (Figure 8-2).

In sexual multicellular organisms,

development usually begins with a fertilized

egg that divides mitotically to

produce a many-celled embryo. These

cells then undergo extensive rearrangements

and interact with one another

to generate the animal’s body

plan and all of the many kinds of specialized

cells in the body. This generation

of cellular diversity is not defined

all at once but is formed as the result

of a hierarchy of developmental

decisions. The many familiar cell

types that make up the body do not

simply “unfold” at some point, but

arise from conditions created in preceding

stages. At each stage of development

new structures arise from the

interaction of less committed rudiments.

Each interaction is increasingly

restrictive, and the decision made at

each stage in the hierarchy further limits

developmental fate. Once cells

embark on a course of differentiation,

they become irrevocably committed to

that course. They no longer depend on

the stage that preceded them, nor do

they have the option of becoming

something different. Once a structure

becomes committed it is said to be determined. Thus the hierarchy of

commitment is progressive and it is

usually irreversible. The two basic

processes that are responsible for this

progressive subdivision are cytoplasmic

localization and induction. We

will discuss both processes as we

proceed through this section.

|

| Figure 8-1 Preformed human infant in sperm as imagined by seventeenth-century Dutch histologist Niklass Hartsoeker, one of the first to observe sperm with a microscope of his own construction. Other remarkable pictures published during this period depicted the figure sometimes wearing a nightcap! |

In 1759 German embryologist Kaspar Friedrich Wolff clearly showed that in the earliest developmental stages of the chick, there was no preformed individual, only undifferentiated granular material that became arranged into layers. These layers continued to thicken in some areas, to become thinner in others, to fold, and to segment, until the body of the embryo appeared. Wolff called this process epigenesis (“origin upon or after”), an idea that a fertilized egg contains building material only, somehow assembled by an unknown directing force. Current ideas of development are essentially epigenetic in concept, although we know far more about what directs growth and differentiation.

|

| Figure 8-2 Key events in animal development. |