Listeria, Bacillus, Corynebacterium and environmental mycobacteria

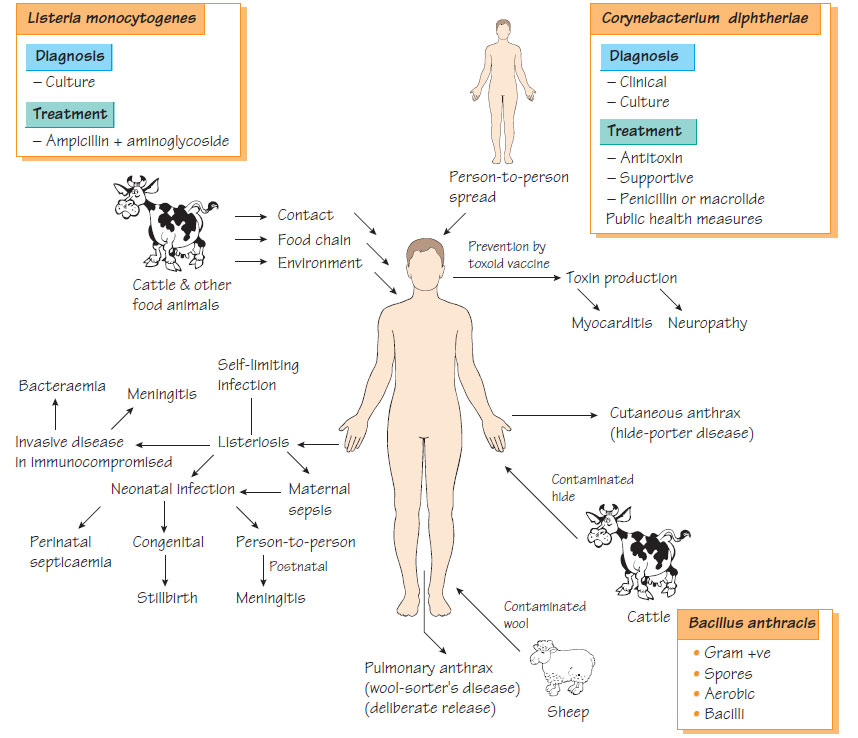

ListeriaListeria are important Gram-positive organisms that can grow at low temperatures (4-10°C); Listeria monocytogenes is associated with human disease.

Epidemiology

Listeria spp. are found in soil or animal faeces and can contaminate foodstuffs. Infection follows consumption of contaminated food; inadequately pasteurized foods and contaminated foods stored in the fridge are at risk.

Listeria monocytogenes infection is usually a mild, self-limiting, infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome. Rarely acute pyogenic meningitis, bacteraemia or encephalitis can develop and these conditions carry a high mortality rate, particularly in patients with reduced cell-mediated immunity. Bacteraemia occurring in pregnancy is associated with intrauterine death, premature labour and neonatal infection similar to that seen with group B streptococci (see Congenital and perinatal infections).

Laboratory diagnosis

Diagnosis is by culture on simple laboratory media and further identification is made by biochemical testing. Typing is achieved by multilocus sequence typing (MLST).

Management

Listeria spp. are susceptible to ampicillin and gentamicin but resistant to the cephalosporins, penicillin and chloramphenicol. Patients with symptoms of meningitis, in whom listeriosis is a possible diagnosis, should receive a drug regimen that incorporates ampicillin.

Listeriosis is controlled by food hygiene, effective refrigeration and adequate reheating of pre-prepared food. Individuals at particular risk, such as pregnant women and immunocompromised patients, should avoid high-risk foods.

Corynebacterium spp.

Corynebacterium jeikeium

This organism, which is naturally resistant to most antibiotics except vancomycin, colonises prostheses and intravenous lines causing infection and bacteraemia, usually in immunocompromised individuals.

Other corynebacteria and related organisms

Rarely, Corynebacterium ulcerans can carry the phage that encodes diphtheria toxin and may cause a diphtheria-like pharyngitis. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis may cause suppurative granulomatous lymphadenitis. Rhodococcus equi has been associated with a severe cavitating pneumonia in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria

Different species may cause localized or disseminated disease in immunocompromised patients. Some may infect prosthetic devices.

The mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAIC) includes Mycobacterium avium, M. intracellulare and M. scrofulaceum, some being natural pathogens of birds, others being environmental saprophytes. They are a common cause of mycobacterial lymphadenitis in children, also causing osteomyelitis in immunocompromised patients and chronic pulmonary infection in the elderly. In the advanced stages of AIDS, they cause disseminated infection and bacteraemia. MAIC is naturally resistant to many antituberculosis agents and treatment with multidrug regimens that include rifabutin, clarithromycin and ethambutol is usually required. Lymphadenitis may require surgery.

These species cause an indolent pulmonary infection that resembles tuberculosis in individuals predisposed by chronic lung disease that has caused deranged pulmonary anatomy (e.g. bronchiectasis, silicosis and obstructive airways disease). Initial therapy with standard drugs may have to be adjusted following the results of bacterial identification and susceptibility tests.

Bacillus

The spores produced by these Gram-positive aerobic bacilli allow them to survive in adverse environmental conditions.

Bacillus anthracis is a soil organism that, under certain climatic conditions, multiplies to cause anthrax in herbivores. Humans can become infected from contaminated animal products. Pathogenicity depends on three bacterial antigens: the 'protective antigen', the oedema factor (both of which are toxins) and the antiphagocytic poly D-glutamic acid capsule. Inoculation of B. anthracis into minor skin abrasions produces a necrotic, oedematous ulcer with regional lymphadenopathy. Inhalation of anthrax spores develops into fulminant pneumonia and septicaemia. An outbreak in 2001 that was caused by deliberate release of the organism has led to the recognition of anthrax as an agent of bioterrorism. The spores of the organisms are prepared in a way that makes them readily aerosolized so that they spread rapidly, infecting many by the respiratory route.

Bacillus cereus

Bacillus cereus produces a heat-stable toxin. Typically, it multiplies in parboiled rice and other contaminated food products, causing a self-limiting food poisoning: vomiting occurs 6 h after exposure, followed by diarrhoea (18 h).