Non-sporing anaerobic infections

Non-sporing anaerobes form the major part of the normal human bacterial flora, outnumbering all other organisms in the gut by a factor of 103. They are also found in the genital tract, oropharynx and skin.Anaerobic sepsis

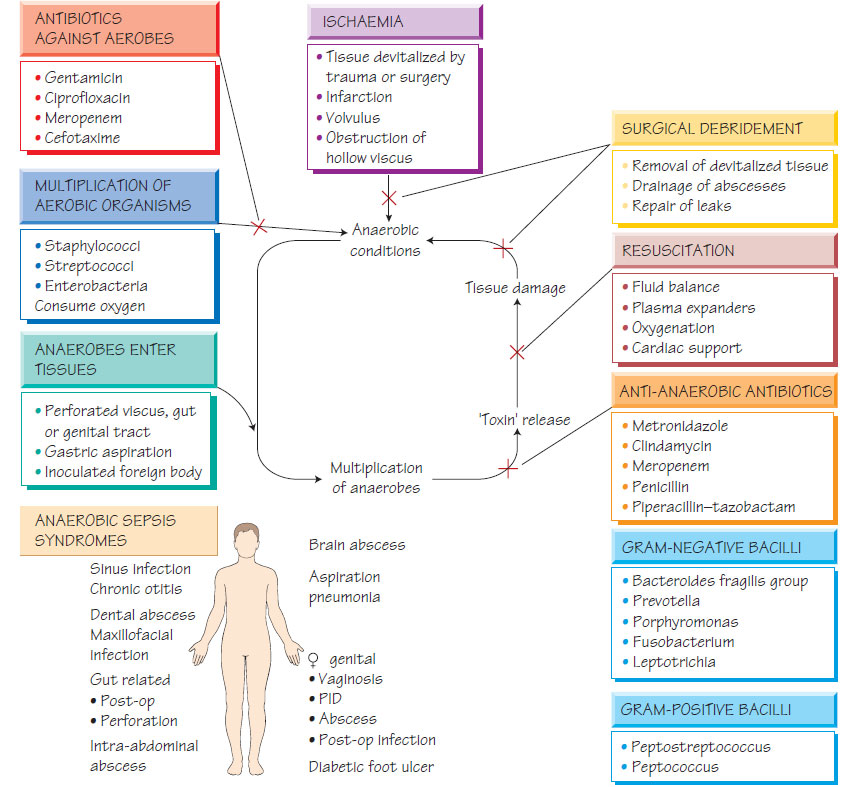

Pathogenesis

- Infection with non-sporing anaerobes is usually endogenous.

- Normal flora may escape into a sterile site following perforation of a hollow viscus (e.g. large intestine).

- Ischaemia (e.g. strangulated hernia) permits anaerobic growth, or the metabolism of facultative bacteria produce anaerobic conditions (e.g. in deep skin ulcers or intraperitoneal infection).

- Once established, anaerobic multiplication is promoted by release of toxic metabolic products and proteolytic enzymes.

- Toxic products of inflammatory cells, such as reactive oxygen intermediates, exacerbate tissue damage creating a vicious cycle of anaerobic sepsis that is rapidly progressive.

- Intra-abdominal sepsis may follow spontaneous bowel perforation or postsurgical leakage and may lead to abscess formation (e.g. abdominal or liver abscesses).

- Sepsis of the female genital tract is often secondary to septic abortion, prolonged rupture of the membranes, complicated caesarean section or retained products of conception.

- Non-sporing anaerobes are implicated in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- Imbalance in the anaerobic flora of the vagina may lead to the non-specific vaginosis syndrome (see Urinary and genital infections).

- Non-sporing anaerobes play a part in polymicrobial liver abscesses and biliary sepsis.

- Pneumonia following aspiration or associated with carcinoma or foreign-body obstruction has a significant anaerobic component and lung abscesses can develop.

- Brain abscesses often have an important anaerobic component.

- Chronic paranasal suppuration, such as in chronic otitis media and chronic sinusitis, may contain non-sporing anaerobes.

- Anaerobes may colonize chronic skin ulcers.

- Rarely tropical ulcers may be caused by Fusobacterium ulcerans.

Non-sporing anaerobes are nutritionally fastidious, sensitive to oxygen and difficult or slow to grow. Specimens should be plated directly in theatre or at the bedside, or transported rapidly to the laboratory in an anaerobic transport system. Pus rather than swabs (which dry out quickly) should be sent. There is an increasing role for nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) based on amplification of the 16S rRNA gene.

Anaerobic species are identified by phenotypic laboratory tests, by studying the end-products of metabolism using gas-liquid chromatography and, increasingly, by molecular means.

Antibiotic susceptibility

Almost all anaerobes are susceptible to metronidazole, although resistance has been reported. Other active agents include meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, penicillin and erythromycin. (Note: Penicillin and erythromycin are not active against Bacteroides fragilis, the anaerobe most commonly isolated from abdominal sepsis.)

Effective management depends on surgery and antimicrobial therapy. Surgical procedures include:

- drainage of abscesses;

- closure of perforations;

- resection of gangrenous tissue;

- debridement of non-viable tissue from ulcers;

- treatment of coexisting infection.

Metronidazole is the most commonly used anti-anaerobic agent.

Prevention and control

The risk of anaerobic infection in elective surgery can be reduced by good operative technique and perioperative antibiotics with anti-anaerobic activity (see Antibacterial therapy and Antibiotics in clinical use).

Bacteroides fragilis is typically associated with postoperative sepsis in abdominal and gynaecological surgery. It also contributes to the polymicrobial flora found in cerebral, hepatic and lung abscesses.

- The most common agent of serious anaerobic sepsis.

- Penicillin resistant through �-lactamase production.

- Produces a protease (DNAse), heparinase and neuraminidase.

- Has an antiphagocytic capsule.

Prevotella melaninogenicus and Fusobacteria are found chiefly in the oral cavity. They are associated with periodontal disease, gingivitis, dental abscess, sinus infection, cerebral and lung abscesses, and necrotizing pneumonia. They are also found in association with Borrelia vincentii in Vincent's angina, and in ulcerative diseases such as cancrum oris (Ludwig's angina), both of which affect the head and neck. They may contribute to anaerobic cellulitis.

Actinomyces spp. are associated with chronic abscesses following dental sepsis, lung abscesses, gut perforation and infection of intrauterine devices. Long-term penicillin is usually effective.