Streptococcal infections

The main characteristics of streptococci include the following.- They are Gram-positive cocci arranged in pairs and chains.

- They are fastidious facultative anaerobes.

- They require rich blood-containing media.

- They may be cultured from the site of infection (throat, wound, etc.) or in blood cultures.

- Colonies are distinguished by haemolysis: complete (β) or incomplete (α) and none (γ).

Streptococcus pyogenes is carried asymptomatically in the pharynx of 5-30% of the population, more commonly in children. It is transmitted by the aerosol route and by contact.

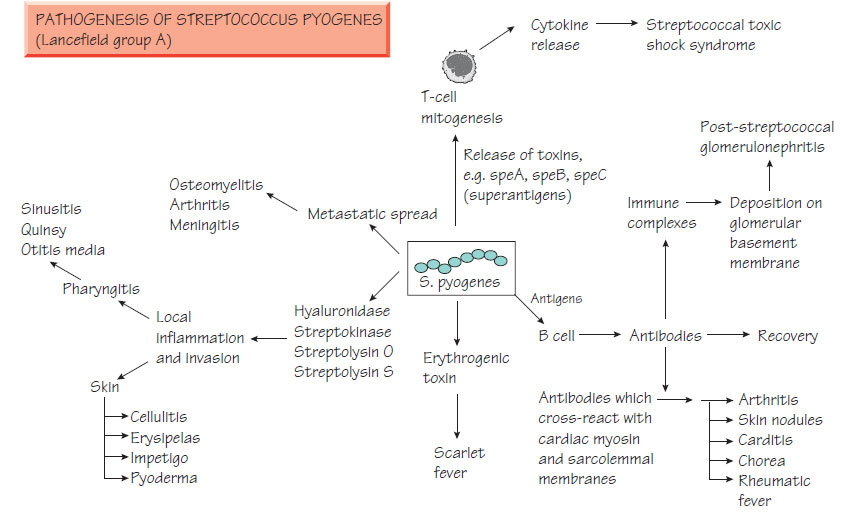

Pathogenesis

Streptococcus pyogenes is surrounded by the M protein antigen, which reduces leucocyte phagocytosis. Antibodies to M proteins are protective but only against infection with the same M type and there are multiple M types. They adhere via fibronectin receptors.

Other features are:

- toxins are important in their pathogenicity:

- erythrogenic toxin associated with scarlet fever;

- pyrogenic exotoxins A, B and C associated with toxic shock;

- production of S. pyogenes cell envelope proteinase (SpyCEP), which degrades IL-8 and other cytokines, thereby retarding neutrophil activation;

- ability to invade and survive intracellularly making them difficult to eradicate with penicillin;

- production of degrading enzymes (immunoglobulin proteases, hyaluronidase and collagenases).

Streptococcus pyogenes, which is an important cause of mortality worldwide, has the following associations:

1 Invasive disease characterized by rapid onset, local tissue destruction and rapid spread within the tissues. Systemic toxicity is common and associated with toxin production. Syndromes include:

- pharyngitis - the most common bacterial cause (see Respiratory tract infections);

- skin infection - erysipelas, impetigo, cellulitis, wound infections and rarely, necrotizing fasciitis or pneumonia (see Infections of the skin and soft tissue);

- puerperal sepsis (see Congenital and perinatal infections);

- complications such as septicaemia and metastatic infections (e.g. osteomyelitis);

- severe toxicity:

- erythrogenic toxin causes scarlet fever;

- pyrogenic toxin-producing strains are associated with streptococcal shock and have a high mortality due to multiple organ failure.

2 Postinfectious immune-mediated diseases which include rheumatic fever, glomerulonephritis and erythema nodosum, are thought to be immune-mediated because antibodies to bacterial structures cross-react with host tissues. Rheumatic fever, now uncommon in developed countries, is a major cause of long-term morbidity and mortality, particularly in areas of poverty and malnutrition.

Streptococcus pyogenes can spread rapidly in surgical and obstetric wards; infected or colonized patients should be isolated in a side room until 48 h after initiation of effective antibiotics. Prompt treatment prevents secondary immune disease (e.g. rheumatic fever). Benzylpenicillin is the treatment of choice and resistance has never been reported. Amoxicillin may be used for oral therapy in less severe infections. Macrolides are an alternative for patients with allergy.

Streptococcus agalactiae

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus) is a commensal in the gut and female genital tract. It causes:

- early perinatal pneumonia or septicaemia;

- later perinatal meningitis;

- puerperal sepsis.

The polysaccharide antiphagocytic capsule is the main pathogenicity determinant. Prophylactic therapy to prevent neonatal disease can be given to those mothers in labour who are febrile, known to be colonized or who have previously had an affected child. There is currently no vaccine available.

Infected neonates may initially lack the classical clinical signs of sepsis, such as fever and the bulging fontanelle of meningitis. A chest X-ray may demonstrate pneumonia, and specimens of blood, CSF, amniotic fluid and gastric aspirate should be cultured. Antigen detection tests are available and can be applied to body fluids for rapid diagnosis.

Treatment and prevention

Neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis requires empirical therapy that includes a penicillin and an aminoglycoside. Perinatal penicillin can prevent invasive infection but should be targeted at babies who are at high risk.

Enterococci possess a group D carbohydrate cell wall antigen and can exhibit all three types of haemolysis (see above). They are principally commensals of the bowel but may cause disease if they become established at other sites. Of more than 12 species, Enterococcus faecalis and E. faecium are the most common members to act as human pathogens, causing urinary tract infection, wound infection and endocarditis. Enterococci are emerging as hospital pathogens, with some species (e.g. E. faecium) now resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Most strains are sensitive to ampicillin/ amoxicillin; however, resistance levels are increasing. Some enterococci have developed resistance to glycopeptides by the acquisition of an alternative peptidoglycan transpeptidation enzyme (the van A or van C system) that alters the usual Ala-DAla cross-linkage so it is not glycopeptide susceptible. Such strains may require therapy with drugs such as linezolid, daptomycin or pristinamycin.