Common Descent

|

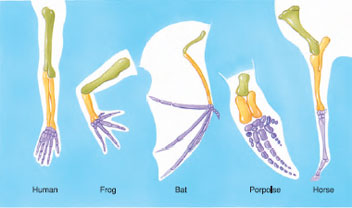

| Figure 6-13 Forelimbs of five vertebrates show

skeletal homologies: green, humerus; yellow, radius and ulna; purple, “hand” (carpals, metacarpals, and phalanges). Clear homologies of bones and patterns of connection are evident despite evolutionary modification for various particular functions. |

Darwin proposed that all plants and animals have descended from an ancestral form into which life was first breathed. Life’s history is depicted as a branching tree, called a phylogeny. Pre-Darwinian evolutionists, including Lamarck, advocated multiple independent origins of life, each of which gave rise to lineages that changed through time without extensive branching. Like all good scientific theories, common descent makes several important predictions that can be tested and potentially used to reject it. According to this theory, we should be able to trace the genealogies of all modern species backward until they converge on ancestral lineages shared with other species, both living and extinct.

We should be able to continue this process, moving farther backward through evolutionary time, until we reach the primordial ancestor of all life on earth. All forms of life, including many extinct forms that represent dead branches, will connect to this tree somewhere. Although reconstructing the history of life in this manner may seem almost impossible, phylogenetic research has been extraordinarily successful. How has this difficult task been accomplished?