Darwin’s Great Voyage of Discovery

Darwin’s Great Voyage

of Discovery

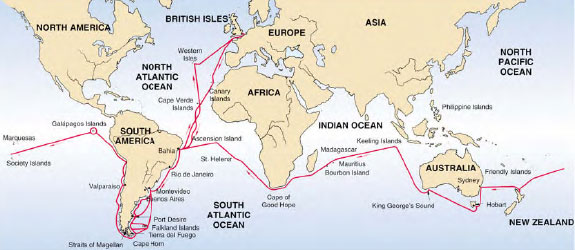

“After having been twice driven back

by heavy southwestern gales, Her

Majesty’s ship Beagle, a ten-gun brig,

under the command of Captain Robert

FitzRoy, R.N., sailed from Devonport

on the 27th of December, 1831.” Thus

began Charles Darwin’s account of the

historic five-year voyage of the Beagle around the world (Figure 6-4). Darwin,

not quite 23 years old, had been asked

to accompany Captain FitzRoy on the Beagle, a small vessel only 90 feet in

length, which was about to depart on

an extensive surveying voyage to

South America and the Pacific (Figure

6-5). It was the beginning of one of

the most important voyages of the

nineteenth century.

During the voyage (1831 to 1836), Darwin endured seasickness and the erratic companionship of the authoritarian Captain FitzRoy. But Darwin’s youthful physical strength and early training as a naturalist equipped him for his work. The Beagle made many stops along the harbors and coasts of South America and adjacent regions. Darwin made extensive collections and observations on the fauna and flora of these regions. He unearthed numerous fossils of animals long extinct and noted the resemblance between fossils of the South American pampas and the known fossils of North America. In the Andes he encountered seashells embedded in rocks at 13,000 feet. He experienced a severe earthquake and watched mountain torrents that relentlessly wore away the earth. These observations strengthened his conviction that natural forces were responsible for the geological features of the earth.

In mid-September of 1835, the Beagle arrived at the Galápagos

Islands, a volcanic archipelago straddling

the equator 600 miles west of

Ecuador (Figure 6-6). The fame of the

islands stems from their infinite

strangeness. They are unlike any other

islands on earth. Some visitors today

are struck with awe and wonder, others

with a sense of depression and

dejection. Circled by capricious currents,

surrounded by shores of twisted

lava, bearing skeletal brushwood baked

by the equatorial sun, almost devoid of

vegetation, inhabited by strange reptiles

and by convicts stranded by the

Ecuadorian government, the islands

indeed had few admirers among

mariners. By the middle of the seventeenth

century, the islands were

already known to the Spaniards as “Las

Islas Galápagos”—the tortoise islands.

The giant tortoises, used for food first

by buccaneers and later by American

and British whalers, sealers, and ships

of war, were the islands’ principal

attraction. At the time of Darwin’s visit,

the tortoises already were heavily

exploited.

During the Beagle’s five-week visit to the Galápagos, Darwin began to develop his views of the evolution of life on earth. His original observations of the giant tortoises, marine iguanas, mockingbirds, and ground finches, all contributed to the turning point in Darwin’s thinking. plants and animals were related to those of the South American mainland, yet differed from them in curious ways. Each island often contained a unique species that was related to forms on other islands. In short, Galápagos life must have originated in continental South America and then undergone modification in the various environmental conditions of the different islands. He concluded that living forms were neither divinely created nor immutable; they were, in fact, the products of evolution. Although Darwin devoted only a few pages to Galápagos animals and plants in his monumental On the Origin of Species, published more than two decades later, his observations on the unique character of the animals and plants were, in his own words, the “origin of all my views.”

On October 2, 1836, the Beagle returned to England, where Darwin

conducted the remainder of his scientific

work (Figure 6-7). Most of

Darwin’s extensive collections had preceded

him there, as had most of his

notebooks and diaries kept during the

cruise. Darwin’s journal was published

three years after the Beagle’s return to

England. It was an instant success and

required two additional printings within

the first year. In later versions, Darwin

made extensive changes and titled his

book The Voyage of the Beagle. The

fascinating account of his observations

written in a simple, appealing style has

made the book one of the most lasting

and popular travel books.

Curiously, the main product of Darwin’s voyage, his theory of evolution, did not appear in print for more than 20 years after the Beagle’s return. In 1838, he “happened to read for amusement” an essay on populations by T. R. Malthus (1766 to 1834), who stated that animal and plant populations, including human populations, tend to increase beyond the capacity of the environment to support them. Darwin already had been gathering information on artificial selection of animals under domestication by humans. After reading Malthus’s article, Darwin realized that a process of selection in nature, a “struggle for existence” because of overpopulation, could be a powerful force for evolution of wild species.

He allowed the idea to develop in his own mind until it was presented in 1844 in a still-unpublished essay. Finally in 1856, he began to assemble his voluminous data into a work on the origin of species. He expected to write four volumes, a very big book, “as perfect as I can make it.” However, his plans were to take an unexpected turn.

In 1858, he received a manuscript from Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 to 1913), an English naturalist in Malaya with whom he was corresponding. Darwin was stunned to find that in a few pages, Wallace summarized the main points of the natural selection theory on which Darwin had been working for two decades. Rather than withhold his own work in favor of Wallace as he was inclined to do, Darwin was persuaded by two close friends, the geologist Lyell and the botanist Hooker, to publish his views in a brief statement that would appear together with Wallace’s paper in the Journal of the Linnean Society. Portions of both papers were read before an unimpressed audience on July 1, 1858.

“Whenever I have found that I have blundered, or that my work has been imperfect, and when I have been contemptuously criticized, and even when I have been overpraised, so that I have felt mortified, it has been my greatest comfort to say hundreds of times to myself that ‘I have worked as hard and as well as I could, and no man can do more than this.’”Charles Darwin, in his autobiography, 1876.

For the next year, Darwin worked urgently to prepare an “abstract” of the planned four-volume work. This book was published in November 1859, with the title On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. The 1250 copies of the first printing were sold the first day! The book instantly generated a storm that has never completely abated. Darwin’s views were to have extraordinary consequences on scientific and religious beliefs and remain among the greatest intellectual achievements of all time.

Once Darwin’s caution had been swept away by the publication of On the Origin of Species, he entered an incredibly productive period of evolutionary thinking for the next 23 years, producing book after book. He died on April 19, 1882, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. The little Beagle had already disappeared, having been retired in 1870 and presumably dismantled for scrap.

|

| Figure 6-5 Charles Darwin and H.M.S. Beagle. A, Darwin in 1840, four years after the Beagle returned to England, and a year after his marriage to his cousin, Emma Wedgwood. B, The H.M.S. Beagle sails in Beagle Channel, Tierra del Fuego, on the southern tip of South America in 1833. The watercolor was painted by Conrad Martens, one of two official artists during the voyage of the Beagle. |

During the voyage (1831 to 1836), Darwin endured seasickness and the erratic companionship of the authoritarian Captain FitzRoy. But Darwin’s youthful physical strength and early training as a naturalist equipped him for his work. The Beagle made many stops along the harbors and coasts of South America and adjacent regions. Darwin made extensive collections and observations on the fauna and flora of these regions. He unearthed numerous fossils of animals long extinct and noted the resemblance between fossils of the South American pampas and the known fossils of North America. In the Andes he encountered seashells embedded in rocks at 13,000 feet. He experienced a severe earthquake and watched mountain torrents that relentlessly wore away the earth. These observations strengthened his conviction that natural forces were responsible for the geological features of the earth.

|

| Figure 6-4 Five-year voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. |

|

| Figure 6-6 The Galápagos Islands viewed from the rim of a volcano. |

During the Beagle’s five-week visit to the Galápagos, Darwin began to develop his views of the evolution of life on earth. His original observations of the giant tortoises, marine iguanas, mockingbirds, and ground finches, all contributed to the turning point in Darwin’s thinking. plants and animals were related to those of the South American mainland, yet differed from them in curious ways. Each island often contained a unique species that was related to forms on other islands. In short, Galápagos life must have originated in continental South America and then undergone modification in the various environmental conditions of the different islands. He concluded that living forms were neither divinely created nor immutable; they were, in fact, the products of evolution. Although Darwin devoted only a few pages to Galápagos animals and plants in his monumental On the Origin of Species, published more than two decades later, his observations on the unique character of the animals and plants were, in his own words, the “origin of all my views.”

|

| Figure 6-7 Darwin’s study at Down House in Kent, England, is preserved today much as it was when Darwin wrote The Origin of Species. |

Curiously, the main product of Darwin’s voyage, his theory of evolution, did not appear in print for more than 20 years after the Beagle’s return. In 1838, he “happened to read for amusement” an essay on populations by T. R. Malthus (1766 to 1834), who stated that animal and plant populations, including human populations, tend to increase beyond the capacity of the environment to support them. Darwin already had been gathering information on artificial selection of animals under domestication by humans. After reading Malthus’s article, Darwin realized that a process of selection in nature, a “struggle for existence” because of overpopulation, could be a powerful force for evolution of wild species.

He allowed the idea to develop in his own mind until it was presented in 1844 in a still-unpublished essay. Finally in 1856, he began to assemble his voluminous data into a work on the origin of species. He expected to write four volumes, a very big book, “as perfect as I can make it.” However, his plans were to take an unexpected turn.

In 1858, he received a manuscript from Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 to 1913), an English naturalist in Malaya with whom he was corresponding. Darwin was stunned to find that in a few pages, Wallace summarized the main points of the natural selection theory on which Darwin had been working for two decades. Rather than withhold his own work in favor of Wallace as he was inclined to do, Darwin was persuaded by two close friends, the geologist Lyell and the botanist Hooker, to publish his views in a brief statement that would appear together with Wallace’s paper in the Journal of the Linnean Society. Portions of both papers were read before an unimpressed audience on July 1, 1858.

“Whenever I have found that I have blundered, or that my work has been imperfect, and when I have been contemptuously criticized, and even when I have been overpraised, so that I have felt mortified, it has been my greatest comfort to say hundreds of times to myself that ‘I have worked as hard and as well as I could, and no man can do more than this.’”Charles Darwin, in his autobiography, 1876.

For the next year, Darwin worked urgently to prepare an “abstract” of the planned four-volume work. This book was published in November 1859, with the title On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. The 1250 copies of the first printing were sold the first day! The book instantly generated a storm that has never completely abated. Darwin’s views were to have extraordinary consequences on scientific and religious beliefs and remain among the greatest intellectual achievements of all time.

Once Darwin’s caution had been swept away by the publication of On the Origin of Species, he entered an incredibly productive period of evolutionary thinking for the next 23 years, producing book after book. He died on April 19, 1882, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. The little Beagle had already disappeared, having been retired in 1870 and presumably dismantled for scrap.