Ontogeny, Phylogeny, and Recapitulation

Ontogeny, Phylogeny, and

Recapitulation

Ontogeny is the history of the development of an organism through its entire life. Early developmental and embryological features contribute greatly to our knowledge of homology and common descent. Comparative studies of ontogeny show how the evolutionary alteration of developmental timing generates new characteristics, thereby producing evolutionary divergence among lineages.

The German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, a contemporary of Darwin, believed that each successive stage in the development of an individual represented one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history. The human embryo with gill depressions in the neck was believed, for example, to resemble the adult appearance of a fishlike ancestor. On this basis Haeckel gave his generalization: ontogeny (individual development) recapitulates (repeats) phylogeny (evolutionary descent). This notion later became known simply as recapitulation or the biogenetic law. Haeckel based his biogenetic law on the flawed premise that evolutionary change occurs by successively adding new features onto the end of an unaltered ancestral ontogeny while condensing the ancestral ontogeny into earlier developmental stages. This notion was based on Lamarck’s concept of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

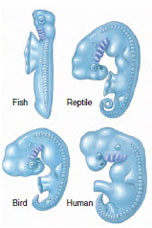

The nineteenth-century embryologist,

K. E. von Baer, gave a more satisfactory

explanation of the relationship

between ontogeny and phylogeny. He

argued that early developmental features

were simply more widely shared

among different animal groups than

later ones. Figure 6-16 shows, for

example, the early embryological similarities

of organisms whose adult forms

are very different (see Figure 8-19) The adults of animals with relatively

short and simple ontogenies

often resemble pre-adult stages of

other animals whose ontogeny is more

elaborate, but embryos of descendants

do not necessarily resemble the adults

of their ancestors. Even early development

undergoes evolutionary divergence

among lineages, however, and it

is not quite as stable as von Baer

believed.

We now know that there are many parallels between ontogeny and phylogeny, but

features of an ancestral

ontogeny can be shifted either to earlier

or later stages in descendant ontogenies.

Evolutionary change in timing of

development is called heterochrony,

a term initially used by Haeckel to

denote exceptions to recapitulation. If a

descendant’s ontogeny extends beyond

its ancestral one, new characteristics

can be added late in development,

beyond the point at which development

would have terminated in

the evolutionary ancestor. Features

observed in the ancestor often are

moved to earlier stages of development

in this process, and ontogeny therefore

does recapitulate phylogeny to some

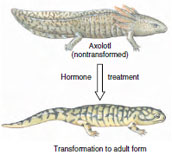

degree. Ontogeny also can be shortened

during evolution, however. Terminal

stages of the ancestor’s ontogeny

may be deleted, causing adults of

descendants to resemble pre-adult

stages of their ancestors (Figure 6-17).

This outcome reverses the parallel

between ontogeny and phylogeny (reverse

recapitulation) producing paedomorphosis

(the retention of ancestral

juvenile characters by descendant

adults). Because lengthening or shortening

of ontogeny can change different

parts of the body independently,

we often see a mosaic of different

kinds of developmental evolutionary

change in a single lineage. Therefore,

cases in which an entire ontogeny

recapitulates phylogeny are rare.

Ontogeny is the history of the development of an organism through its entire life. Early developmental and embryological features contribute greatly to our knowledge of homology and common descent. Comparative studies of ontogeny show how the evolutionary alteration of developmental timing generates new characteristics, thereby producing evolutionary divergence among lineages.

The German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, a contemporary of Darwin, believed that each successive stage in the development of an individual represented one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history. The human embryo with gill depressions in the neck was believed, for example, to resemble the adult appearance of a fishlike ancestor. On this basis Haeckel gave his generalization: ontogeny (individual development) recapitulates (repeats) phylogeny (evolutionary descent). This notion later became known simply as recapitulation or the biogenetic law. Haeckel based his biogenetic law on the flawed premise that evolutionary change occurs by successively adding new features onto the end of an unaltered ancestral ontogeny while condensing the ancestral ontogeny into earlier developmental stages. This notion was based on Lamarck’s concept of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

|

| Figure 6-16 Comparison of gill arches of different embryos. All are shown separated from the yolk sac. Note the remarkable similarity of the four embryos at this early stage in development. |

We now know that there are many parallels between ontogeny and phylogeny, but

|

| Figure 6-17 Aquatic and terrestrial forms of axolotls. Axolotls retain the juvenile, aquatic morphology (above) throughout their lives unless forced to metamorphose (below) by hormone treatment. Axolotls evolved from metamorphosing ancestors, an example of paedomorphosis. |