Nonallopatric Speciation

Nonallopatric Speciation

Can speciation ever occur without

prior geographic separation of populations?

Allopatric speciation may seem

an unlikely explanation for situations

where many closely related species

occur together in restricted areas that

have no traces of physical barriers to

animal dispersal. For example, several

large lakes around the world contain

very large numbers of closely related

species of fish. The great lakes of

Africa (Lake Malawi, Lake Tanganyika,

and Lake Victoria) each contain many

species of cichlid fishes that are found

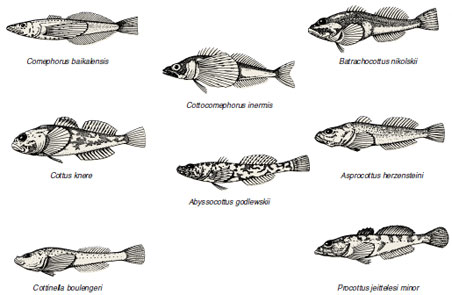

nowhere else. Likewise, Lake Baikal in

SIiberia contains many different species

of sculpins that occur nowhere else in

the world (Figure 6-20). It is difficult

to conclude that these species arose

anywhere other than in the lakes

they inhabit, and yet those lakes are

young on an evolutionary timescale

and have no obvious environmental

barriers that would fragment fish

populations.

To explain speciation of fish in freshwater lakes and other examples like these, sympatric (“same land”) speciation has been hypothesized. According to this hypothesis, different individuals within a species become specialized for occupying different components of the environment. By seeking out and using very specific habitats in a single geographic area, different populations achieve sufficient physical and adaptive separation to evolve reproductive barriers. For example, cichlid species of African lakes are very different from each other in their feeding specializations. In many parasitic organisms, particularly parasitic insects, different populations may use different host species, thereby providing the physical separation necessary for reproductive barriers to evolve. Supposed cases of sympatric speciation have been criticized, however, because the reproductive distinctness of the different populations often is not well demonstrated, so that we may not be observing formation of distinct evolutionary lineages that will become different species.

The occurrence of sudden sympatric speciation is perhaps most likely among higher plants. Between one-third and one-half of flowering plant species may have evolved by polyploidy (doubling of chromosome numbers), without prior geographic isolation of populations. In animals, however, speciation through polyploidy is an exceptional event.

|

| Figure 6-20 The sculpins of Lake Baikal, products of speciation that occurred within a single lake. |

To explain speciation of fish in freshwater lakes and other examples like these, sympatric (“same land”) speciation has been hypothesized. According to this hypothesis, different individuals within a species become specialized for occupying different components of the environment. By seeking out and using very specific habitats in a single geographic area, different populations achieve sufficient physical and adaptive separation to evolve reproductive barriers. For example, cichlid species of African lakes are very different from each other in their feeding specializations. In many parasitic organisms, particularly parasitic insects, different populations may use different host species, thereby providing the physical separation necessary for reproductive barriers to evolve. Supposed cases of sympatric speciation have been criticized, however, because the reproductive distinctness of the different populations often is not well demonstrated, so that we may not be observing formation of distinct evolutionary lineages that will become different species.

The occurrence of sudden sympatric speciation is perhaps most likely among higher plants. Between one-third and one-half of flowering plant species may have evolved by polyploidy (doubling of chromosome numbers), without prior geographic isolation of populations. In animals, however, speciation through polyploidy is an exceptional event.