Perpetual Change

Darwinian

Evolutionary

Theory: The

Evidence

Perpetual Change

The main premise underlying Darwinian

evolution is that the living world

is neither constant nor perpetually

cycling, but always changing. Perpetual

change in the form and diversity of animal

life throughout its 600- to 700-

million-year history is seen most directly

in the fossil record. A fossil is a remnant

of past life uncovered from the

crust of the earth (Figure 6-8). Some

fossils constitute complete remains

(insects in amber and mammoths),

actual hard parts (teeth and bones),

and petrified skeletal parts that are infiltrated

with silica or other minerals

(ostracoderms and molluscs). Other

fossils include molds, casts, impressions,

and fossil excrement (coprolites).

In addition to documenting organismal

evolution, fossils reveal profound

changes in the earth’s environment,

including major changes in the distributions

of lands and seas. Because many

organisms left no fossils, a complete

record of the past is always beyond our

reach; nonetheless, discovery of new

fossils and reinterpretation of existing

ones expand our knowledge of how

the form and diversity of animals

changed through geological time.

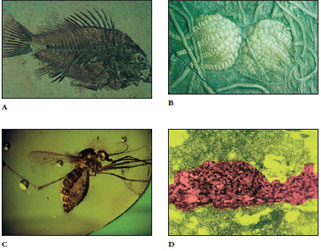

Fossil remains may on rare occasions include soft tissues preserved so well that recognizable cellular organelles can be viewed by electron microscopy! Insects are frequently found entombed in amber, the fossilized resin of trees. One study of a fly entombed in 40-million-year-old amber revealed structures corresponding to muscle fibers, nuclei, ribosomes, lipid droplets, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria (Figure 6-8D).This extreme case of mummification probably occurred because chemicals in the plant sap diffused into the embalmed insect’s tissues

Perpetual Change

|

| Figure 6-8 Four examples of fossil material. A, Fish fossil from rocks of the Green River Formation, Wyoming. Such fish swam here during the Eocene epoch of the Tertiary period, approximately 55 million years ago. B, Stalked crinoids (class Crinoidea) from 85-million-year-old Cretaceous rocks. The fossil record of these echinoderms shows that they reached their peak millions of years earlier and began a slow decline to the present. C, An insect fossil that got stuck in the resin of a tree 40 million years ago and that has since hardened into amber. D, Electron micrograph of tissue from a fly fossilized as shown in C; the nucleus of a cell is marked in red. |

Fossil remains may on rare occasions include soft tissues preserved so well that recognizable cellular organelles can be viewed by electron microscopy! Insects are frequently found entombed in amber, the fossilized resin of trees. One study of a fly entombed in 40-million-year-old amber revealed structures corresponding to muscle fibers, nuclei, ribosomes, lipid droplets, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria (Figure 6-8D).This extreme case of mummification probably occurred because chemicals in the plant sap diffused into the embalmed insect’s tissues