Using chemicals

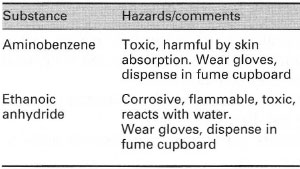

Safety aspectsIn practical classes, the person in charge has the responsibility to inform you of any hazards associated with the use of chemicals. In project work, your first duty when using an unfamiliar chemical is to find out about its properties, especially those relating to safety. For routine practical procedures, a risk assessment may have been carried out by a member of staff and the relevant safety information may be included in the practical schedule: an example is shown in Table 4.1. If not, you will have to carry out a risk assessment before you begin. Before you use any of the chemicals, you must find out whether safety precautions need to be taken and complete the appropriate forms confirming that you appreciate the risks involved. Your department must provide the relevant information to allow you to do this. If your supervisor has filled out the form, read it carefully before signing.

Key safety points when handling chemicals are:

|

|

Selection

Chemicals are supplied in varying degrees of purity and this is always stated on the manufacturer's containers. Suppliers differ in the names given to the grades and there is no conformity in purity standards. Very pure chemicals cost more, often very much more, and should only be used when the situation demands. If you need to order a chemical, your department will have a defined procedure for doing this.

Preparing solutions Solutions are usually prepared with respect to their molar concentrations (e.g. mol L-1, mol dm-3, or mol m-3) or mass concentrations (e.g. gL-1, or kg m-3): both can be regarded as an amount (usually mass) per unit volume, in accordance with the relationship:

⇒Equation [4.1]

| concentration = | amount |

| volume |

The most important aspect of eqn [4.1] is to recognize clearly the units involved, and to prepare the solution accordingly: for molar concentrations you will need the relative molecular mass of the chemical, so that you can calculate the mass of substance required.

In general there are two levels of accuracy required for the preparation of solutions:

- General-purpose solutions - solutions of chemicals used in qualitative

and preparative procedures (p. 17) when the concentration of the

chemical need not be known to more than one or two decimal places.

For example:

- solutions used in extraction and washing processes, e.g. hydrochloric acid (0.l mol L-1), sodium hydroxide (2M), sodium carbonate (5% w/v);

- solutions of chemicals used in preparative experiments where the techniques of purification - distillation, recrystallization, filtration, etc. - introduce intrinsic losses of substances that make accuracy to any greater level meaningless.

- Analytical solutions - solutions used in quantitative analytical procedures

when the concentration needs to be known to an accuracy of four

decimal places (e.g. 0.0001 mol L-1). For example in:

- volumetric procedures (titrations) and gravimetric analysis, where the concentrations of standard solutions of reagents and compounds to be analysed need to be accurately known;

- spectroscopy, e.g. quantitative UV and visible spectroscopy, atomic absorption spectroscopy and flame photometry;

- electrochemical measurements: pH titrations, conductance measurements and polarography;

- chromatographic methods.