Mycobacteria

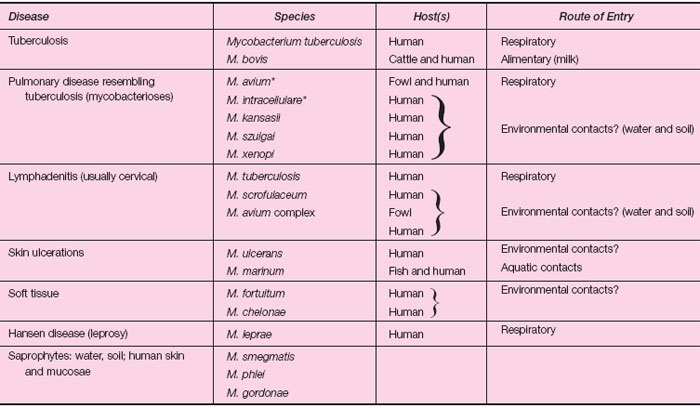

The genus Mycobacterium contains many species, a number of which can cause human disease. A few are saprophytic organisms, found in soil and water, and also on human skin and mucous membranes. The two important pathogens in this group are Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the agent of tuberculosis, and Mycobacterium leprae, the cause of Hansen disease (leprosy). However, Mycobacterium kansasii and the Mycobacterium avium complex (see table 29.1) cause disease in persons with chronic lung disease and are being seen more frequently as opportunistic pathogens in patients with leukemia and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Table 29.1 summarizes some of the mycobacteria that are human pathogens according to the type of disease that they may cause. Species of mycobacteria that are commensals and not normally associated with human disease are listed as well.Laboratory diagnosis of tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infection is made by identifying the organisms in acid-fast smears and in cultures of clinical specimens from any area of the body where infection may be localized. In pulmonary disease, sputum specimens and gastric washings are appropriate, but if the disease is disseminated, the organisms may be found in a variety of areas. Urine, blood, spinal fluid, lymph nodes, or bone marrow may be of diagnostic value, especially in immunocompromised patients. Any specimen collected for identification of mycobacteria must be handled with particular caution and strict asepsis. These organisms, with their thick waxy coats, can survive for long periods even under adverse environmental conditions. They can remain viable for long periods in dried sputum or other infectious discharges and they are also resistant to many disinfectants. Choosing a suitable disinfectant for chemical destruction of tubercle bacilli requires careful consideration.

|

| Table 29.1 Mycobacteria in Infectious Disease |

Clinical samples such as sputum must be digested and concentrated before they are cultured for mycobacteria. During the digestion process, the thick, viscous sputum is liquefied so that any mycobacteria present, particularly if present in low number, are distributed evenly throughout the specimen. After digestion, the sample is centrifuged at high speed to concentrate the mycobacteria at the bottom of the centrifuge tube. The supernatant fluid is discarded into an appropriate disinfectant, and an acid-fast-stained smear of a portion of the centrifuged pellet is prepared and examined microscopically. Another portion is cultured on special mycobacterial culture media. The digestion and concentration steps greatly improve the microscopic detection of mycobacteria in clinical specimens and their recovery in culture. The Kinyoun stain) is commonly used to stain acid-fast bacilli. The organisms stain red against a blue background, whereas non-acid-fast organisms are blue (see colorplate 9). Tubercle bacilli are slender rods, often beaded in appearance. Another stain, using the fluorescent dyes auramine and rhodamine, permits rapid detection of the organisms as bright objects against a dark background (see colorplate 9). This technique is used in many laboratories today because the fluorescing organisms are easier to detect than bacilli stained with the acid-fast method. Thus, the preparation can be scanned at ×400 magnification rather than ×1,000. Most mycobacteria do not grow on conventional laboratory media such as chocolate or blood agar plates. Therefore, special solid media containing complex nutrients, such as eggs, potato, and serum, are used for culture. Lowenstein-Jensen medium is a solid egg medium prepared as a slant and is one of several in common use (see colorplate 39). Broth media are also available. Tubercle bacilli and most other mycobacteria grow very slowly. At least several days, and up to 4 to 8 weeks for M. tuberculosis, are required for visible growth to appear. They are aerobic organisms, but their growth can be accelerated to some extent with increased atmospheric CO2. Automated instruments that detect the CO2 released by mycobacteria are used in many laboratories and permit detection before visible growth is apparent. The CO2 is released when mycobacteria metabolize special substrates present in broth culture media. M. leprae (also known as Hansen bacillus) cannot be cultivated on laboratory media. Laboratory diagnosis of Hansen disease is based only on direct microscopic examination of acidfast smears of material from the lesions.

Most mycobacteria do not grow on conventional laboratory media such as chocolate or blood agar plates. Therefore, special solid media containing complex nutrients, such as eggs, potato, and serum, are used for culture. Lowenstein-Jensen medium is a solid egg medium prepared as a slant and is one of several in common use (see colorplate 39). Broth media are also available.

Tubercle bacilli and most other mycobacteria grow very slowly. At least several days, and up to 4 to 8 weeks for M. tuberculosis, are required for visible growth to appear. They are aerobic organisms, but their growth can be accelerated to some extent with increased atmospheric CO2. Automated instruments that detect the CO2 released by mycobacteria are used in many laboratories and permit detection before visible growth is apparent. The CO2 is released when mycobacteria metabolize special substrates present in broth culture media.

M. leprae (also known as Hansen bacillus) cannot be cultivated on laboratory media. Laboratory diagnosis of Hansen disease is based only on direct microscopic examination of acidfast smears of material from the lesions.