Neisseria

The genus Neisseria contains two pathogenic species and a number of others that are commonly found in the normal flora of the upper respiratory tract. The two medically important species are N. gonorrhoeae, the agent of gonorrhea, and N. meningitidis, an agent of bacterial meningitis. All Neisseria are gram-negative diplococci, indistinguishable from each other in microscopic morphology. The pathogenic species are obligate human parasites and quite fastidious in their growth requirements on artificial media. On primary isolation, they require an increased level of CO2 during incubation at 35°C. The nonpathogenic commensals of the upper respiratory tract are not fastidious and grow readily on simple nutrient media. Some of the respiratory flora, for example, N. subflava and N. flavescens, have a yellow pigment, but most Neisseria produce colorless colonies. All Neisseria are oxidase positive (see colorplate 13), which helps to distinguish them from other genera, but not from each other. Biochemically, the Neisseria species are most readily identified on the basis of their differing patterns of carbohydrate degradation. The cultural differentiation of a few Neisseria species, including the two pathogenic species, is shown in table 27.1-1. Recently, nucleic acid probe tests and gene amplification assays for detecting N. gonorrhoeae directly in patient specimens have become available. These tests can be completed within 2 to 4 hours and thus diagnostic results are available the day the specimen is taken. |

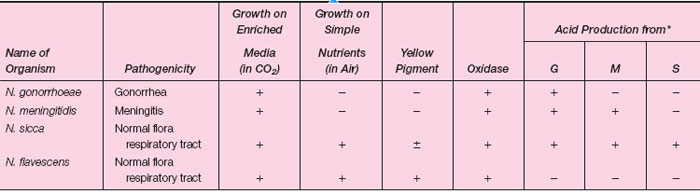

| Table 27.1-1 Differentiation of Some Neisseria species |

Isolation of the organism in culture is still considered the standard test, however, and is always used for potential medical-legal cases such as suspected sexual abuse of children.

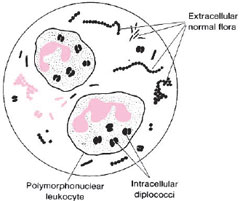

Gonorrhea usually begins as an acute, local infection of the genital tract. In the male, the urethra is initially involved and exudes a purulent discharge. When the exudate is smeared on a microscope slide and Gram stained, it is seen to contain many polymorphonuclear cells (phagocytic white blood cells), some of which contain intracellular, gram-negative diplococci (see colorplate 4). In the female, acute infection usually begins in the cervix. Smears of the exudate show the same intracellular diplococci as seen in males, except that there are often many more extraneous organisms present in specimens collected from females (see fig. 27.1). Indeed, the abundant normal flora of the vagina may mask the presence of gonococci (N. gonorrhoeae) in smears or cultures from females. For many women, initial infection may be asymptomatic. In them, gonococci cannot be demonstrated in smears, and, therefore, culture or other detection techniques, such as nucleic acid probes, or gene amplification assays must be used for laboratory diagnosis. Asymptomatic infection also occurs in a smaller percentage of infected males. Demonstration of N. gonorrhoeae in culture or by a probe or gene amplification test provides definitive proof of infection. For culture, specimens may be taken from the cervix, urethra, anal canal, or throat and one or more of these sites should be swabbed for culture when disease is suspected in women. For male patients, with a urethral discharge, Gram-stained smears of the exudate revealing typical gram-negative intracellular diplococci are considered presumptively diagnostic, and cultures are generally not taken. Figure 27.2 outlines the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Public Health Service, regarding smears and cultures from males and females, indicating all necessary steps to confirm the diagnosis of gonorrhea by these methods.

When swab cultures are taken, a suitable agar medium should be inoculated directly with the swab, the culture placed in a candle jar or CO2 incubator, and incubated at 35°C pending laboratory examination. Media enriched with hemoglobin and other growth factors are in common use (modified Thayer-Martin and NYC medium are examples). Antimicrobial agents are added to suppress the normal flora of mucous membranes and to make these media more selective for gonococci. Following suitable incubation, laboratory identification of N. gonorrhoeae is made by the criteria shown in table 27.1-1(see colorplate 37).

Meningitis, an inflammation of the meninges of the brain, may be caused by a variety of microbial agents. Chief among them is Neisseria meningitidis, a gram-negative diplococcus. The usual portal of entry for these organisms is the upper respiratory tract. They may colonize harmlessly there in the immune individual. When they enter susceptible hosts who cannot keep them localized, they may cause invasive disease, either by finding their way into the bloodstream and then to deep tissues, or by direct extension through the membranous bony structures posterior to the pharynx and sinuses. When they localize on the meninges (the thin membranes that cover the brain), meningococci (N. meningitidis) induce an acute, purulent local infection that may have far-reaching effects in the central nervous system. The laboratory diagnosis of N. meningitidis infections is made by recovering the organism in cultures of spinal fluid, blood, or the

|

| Figure 27.1 Diagram of a microscopic field showing intracellular diplococci within polymorphonuclear cells. In cervical smears, organisms of the normal flora may be numerous, but these are extracellular. |

In practical situations, it is important to remember that pathogenic Neisseria (gonococci and meningococci) are very sensitive to environmental conditions outside the human body, especially temperature and atmosphere. They are easily destroyed in specimens that are:

- delayed in transit to the laboratory,

- kept at temperatures too far below or above 35°C,

- heavily contaminated by normal flora, or

- not promptly provided with an increased CO2 atmosphere (as in a candle jar).

In the following experiment, you will have an opportunity to see the cultural and microscopic properties of some Neisseria species.

| Purpose | To study the microscopic and cultural characteristics of Neisseria species |

| Materials | Sterile petri dish with filter paper Oxidase reagent (dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine) Phenol red broths (glucose, maltose, sucrose) Candle jar, containing preincubated chocolate agar plate cultures of:

positive male patient with gonorrhea) |

Procedures

- Examine the morphology of colonies on each plate and record their appearance, including pigmentation.

- Test representative colonies on each pure culture plate for the enzyme oxidase following the procedure in Experiment 24.5, step 6 (a-c).

- Test representative colonies from the plated clinical specimen for their oxidase reactions. Using a marking pen or pencil, mark the bottom of the plate under colonies that are oxidase positive. Record oxidase reactions in the table under Results.

- Make a Gram stain of an oxidase-positive colony from each of the chocolate plates. Record the microscopic morphology of each in the table under Results.

- Inoculate one oxidase-positive colony from each chocolate agar plate into a glucose, maltose, and sucrose broth tube, respectively.

- From the plated clinical specimen, select one oxidase-negative colony type (if any) and inoculate it into a glucose, maltose, and sucrose broth tube, respectively.

- Incubate all carbohydrate subcultures in a candle jar or CO2 incubator at 35°C for 24 hours. Examine for evidence of acid production. Record results.

Results

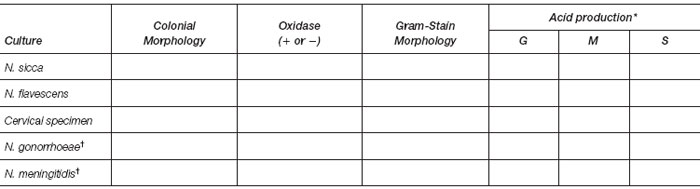

- Record your observations in the table that follows.

*G = glucose; M = maltose; S = sucrose

†To be completed from your reading.

- Laboratory report of clinical specimen: ___________